The decision to set sail in a commercial vessel rests with the captain. A captain with years of experience and training, who is skilled at sailing and navigating in all conditions.

Increasingly, the state of a vessel’s cyber security will affect its seaworthiness. Yet in future we may expect a captain with limited understanding of cyber security to make a decision about that seaworthiness.

The concept of seaworthiness is not new, but has very specific meanings in the context of law and maritime insurance.

Cyber security is not widely understood in the maritime sector, and even more poorly understood by ships crews. This is no surprise – vessels were primarily unconnected entities, exposed only when in port. Satcoms were very expensive. However, with the advent of cheap VSAT, most vessels are now ‘always on’ and require connectivity in order to function efficiently.

Connectivity + old, unmanaged on-board networks = significant cyber risk

Indeed, insurance clause 380 or the ‘Institute cyber attack exclusion clause’ specifically excludes insurance cover where the cause is proven to be cyber-related.

The IMO, BIMCO and various other flags and associations are pushing ‘cyber’ standards at a pace, yet somehow expect ships captains to become cyber savvy. In my experience, many captains are tech-savvy, happy to operate a computer, mobile phone, electronic charts, integrated bridge and plenty more, yet wouldn’t have the first clue how to ensure their ship was cyber secure.

Indeed, we’ve already seen the Korean Register certify the first vessel, the Songa Hawk, as ‘fully compliant in all areas’ of its cyber security certification. I have extensive concerns about this, as we have never tested a vessel which we would consider to be suitably cyber secure, even those fresh out of the yard with the latest systems on board.

So the captain reviews a certificate stating that the vessel is cyber secure and sets sail, thinking that it is cyber-seaworthy. I would love to review the output of a legal case where a vessel cyber certification was proved to be invalid…

After leaving port

Once at sea, we expect the captain’s cyber expertise to move from ‘risk assessor’ to that of ‘incident responder’.

We can teach crews how to behave in a secure manner, reducing risk – there are great, free resources online such as https://www.becyberawareatsea.com/ – however this does not always help them deal with incidents. Many operators will expect the master to make contact with shore operations during a suspected cyber incident for advice. However, any targeted attack against a vessel at sea will likely have come via its satellite communication system. A motivated attacker would simply shut down internet access for all but themselves.

Does the master have access to a completely independent satphone? So often the satphone is actually routed through the same satcom terminal, for reasons of cost efficiency. You should plan for the master having to respond to an incident without any external support.

Safety

We can learn a lot from the approach to safety, which has improved dramatically, partly as a result of SOLAS (safety of lives at sea) regulations.

A vessel is not seaworthy if it:

- Is not appropriately crewed to safety requirements

- Does not have a crew member aboard with responsibility for and sufficient expertise to deal with a cyber security incident?

- Is not physically safe and sound

- Does not have sufficient resources (fuel, stores, etc)

- Is not stable

So, when is it seaworthy? Is it seaworthy if:

- The ballasting system has a security flaw that allows it to be compromised or incorrectly report the stability of the vessel?

- It does not have sufficient cyber security defences to resist attack?

- The hull stress monitoring system is exposed to cyber attack?

- The weather reporting systems have been compromised, delivering incorrect routing data?

Cyber issues can be subtle, buried deep in complex systems that have been modified over the years, through partial refits, through ‘enthusiastic’ engineers accidentally breaking network segregation, through cyber-incompetent support organisations and through maritime technology providers who don’t understand or prioritise cyber security.

These subtle cyber issues have comparisons in physical maritime incidents; for example the slow start-air leak that eventually leaves a vessel immobile, a stuck ballasting cross-flow valve, or a GPS antenna cable breaking, leaving the vessel dead reckoning (see the Royal Majesty incident of June 10, 1995).

Advice for a ship’s master

You won’t be able to ‘see’ all cyber incidents at sea. Unlike the movies, hacking incidents rarely involve a skull and crossbones on your ECDIS!

Here a few tips and probing questions to ask about the cyber seaworthiness of your vessel. This isn’t comprehensive, but if these questions are answered well, you can have some confidence that your operator, support organisation or vessel owner at least have a process for evaluating cyber security.

Network segregation

Above all, you will want to see evidence that the various networks on board the vessel are suitably segregated from each other. If your shore team tells you that they’re all segregated, then they’re not being honest with you!

You want to know which systems on the various networks can connect to each other:

- For example, you’ll want to know that your integrated bridge can communicate with your engine management systems, but not your crew Wi-Fi network.

- You’ll want to know that your business network, for company email etc, can communicate with HQ but not your ECDIS.

- That your ballasting system can be controlled from the ballasting station, potentially from the integrated bridge but not from shore systems via satcoms.

- That your ECDIS can connect to specific, secure resources on the internet to retrieve CMAP chart updates, but not to any old web site.

When the vessel was first laid down, the network was probably fairly robust and simple. Indeed, the only vessels we have tested that are even vaguely cyber-secure are those fresh out of the yard. However, ‘bolting on’ VSAT, refits and changes made by crew often defeat much of the good security that was initially in place. That’s why checking reality vs what is perceived is so important.

Asking the right questions can give the master good insight in to the state of security of the vessel. If the operator or support organisation can’t provide evidence of actual network segregation and controls, then you should have little confidence in their ability to keep your vessel secure.

Updates

Updates fix security issues. Ask for proof that all systems on board are running the latest software and patches. Again, if you are told that everything is up to date, it is unlikely you are being told the truth!

Updates apply to lots of different systems on board, many of which are often overlooked or simply not understood by general IT network specialists:

- Business computers are usually kept up to date automatically with operating system patches, though 3rd party software (e.g. Java, Adobe products etc) is less well updated.

- The ECDIS is just a computer, usually Windows though sometimes Linux. When was the operating system last updated? When was the ECDIS software itself updated?

- The satcom terminal is often overlooked. Numerous security flaws have been found in these, so is it at the latest software version? It rarely is!

- What about the software running in your engine room, controlling your engines and power systems?

- The software versions running on the IT network routers and OT network devices?

- The software running on your wireless routers?

- Your load management software? Your HSMS, ballasting etc. etc.

- Updates fix security issues. A vessel with up to date software is going to be a lot harder to hack than one with aging, vulnerable software.

Passwords

YAWN. Passwords again. How boring.

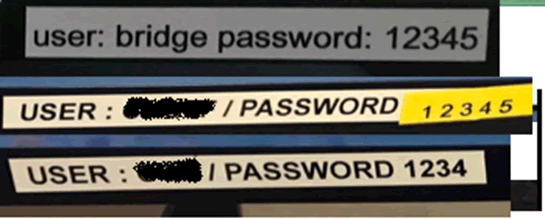

Yet, simple, re-used, default or even blank passwords are the key to almost every vessel and corporate network compromise we have achieved over the last 22 years.

It isn’t necessarily a problem having a password stuck to a monitor on a bridge system, but this should be for a user account, not an administrator account.

It also shouldn’t be a simple password, as a hacker on the network will attempt to crack anything too simple.

Yes, there are ways that hackers can work around this and better ways of managing access to systems (tokens or smartcards for example) but these requires significantly more change to implement.

Ask a few probing questions too:

“What is the password complexity requirement for non-Windows systems?”

- If they try to fob you off with a non-answer such as ‘we won’t disclose the policy’ then I would push harder. Disclosing the password policy isn’t a threat to security, so long as the policy is good

“have the industrial controllers managing the engine had their passwords changed from default”

“are the passwords for the integrated bridge systems changed from the manufacturers default”

“When was the password for the VDR last changed?”

Mitigating controls

There are plenty of changes one can make to delay the spread or reduce the impact of an incident.

For example, a ransomware attack that takes out one ECDIS is less likely to spread to a second ECDIS if it’s a different vendor, has different passwords or is on a different network.

Blocking USB ports on all accessible bridge and engine room systems can help reduce accidental infections. System with USB ports that are needed for updates can be kept behind lock and key.

Detecting GPS tampering can often be achieved by overlaying synthetic radar over the ECDIS, where mismatches between shorelines can be identified, or radar position mismatches of other vessels with their AIS position can be seen.

It’s also easy to check for wireless networks that aren’t authorised. Even walking the vessel with a mobile phone whilst at sea will show up most Wi-Fi access points. Are they legitimate, or has an engineer installed something to allow them to access engine systems from their cabin? Or has another crew member run out of internet allowance and hooked up a back door to the business network to get more access?

Conclusion

It isn’t reasonable to expect a ships master to assess the cyber-seaworthiness of a vessel. They must have tools and resources at their disposal, together with expertise and assistance.

There is far too much ‘bluster’ in the maritime cyber sector; too many self-declared ‘cyber security experts’ driving meaningless checklists.

Certification schemes are limited by the ability of those carrying out the certification. Assessing vessel cyber properly takes a sizeable, rare skillset.

Vessel certification is quickly undermined by changes made, either intentional or otherwise.

Whilst most vessel cyber incidents are currently untargeted ransomware and similar, motivated hackers will ‘follow the money’.