TL; DR

- Covert recording devices are cheap, easy to buy, and easy to use.

- The real risk is not a skilled attacker. It is everyday misuse, motivated by frustration, curiosity, or spite.

- I bought an audio bug for legitimate proof of concept work and found existing recordings already on it.

- Forensics suggested the device had likely been used before it reached me.

- We assess risk based on ease of use and likelihood, not just worst case impact.

A normal shopping trip into ethically dubious kit

As part of physical social engineering engagements, I will often trawl the common online stores for devices that could be abused to gain information. This is not technical abuse. It is using the device as it was designed, but not in the most ethical way.

That often includes things like lockpicks, keyloggers and the star of the story, audio bugs.

I don’t spend a lot of money on these, though I am sure my wife would disagree. My box of “evil gadgets” is similar to some people’s power tool collection. The point is that you do not need to visit the shady end of the internet to find ethically questionable kit. A quick trip down an online marketplace with the right search terms will do it.

The device worked, which was the problem

The audio bug I purchased was inexpensive, well built and designed, compact and easy to use. It did exactly what it said on the packet. No frills, no fancy logos, just plain black and easy to overlook.

When we do this work, we are aware of the legal and moral problems that come with recording someone, or a room of people without consent. In the vast majority of cases when we “use” these devices it is as a proof of concept. They get placed, photographed, and removed. If anything is ever recorded, It is only with express written permission and clear ethical usage guidance to show the ease and effectiveness.

The surprise

My latest purchase came with several existing recordings already on the device!

With some caution I listened. It sounded like someone going about their day. A morning routine, a train journey, what might have been a factory, a lunchtime conversation, then a train home, and an evening with a television or music in the background. The muffled sounds and changes in pitch led me to believe this was in someone’s pocket or purse and may not have been known by them.

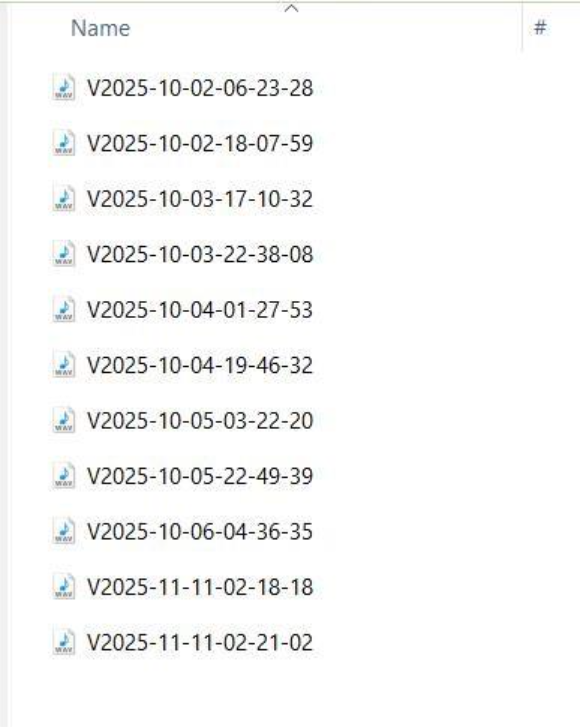

There appeared to be a few days of recordings. Because the device was sound activated, it was sometimes hard to piece together what was happening. The speech sounded like Cantonese, Mandarin, or another language I do not speak, which made it harder to interpret, but not harder to recognise for what it was.

Forensics confirmed it was not just test data

I mentioned this to my colleagues here at PTP, and Andrew Tierney quite rightly asked if these could just be files placed on the device as part of the build process.

That is when our digital forensics team got involved.

An image was pulled from the device and analysed and sure enough, along with the files that were on the device, there were just over 20 other previously deleted files, but none of them were recoverable. It looked very much like the device had been used previously.

Tracing the supplier and the reviews, it also appeared at least one other buyer had reported something similar. It was not the norm, and many reviews were positive, but it was enough to make the point.

The real threat model is boredom, frustration, and misplaced entitlement

This was brought into sharper focus by recent reporting about parents covertly recording teachers in Scotland and posting those recordings online, following a letter to parents asking them not to do it. BBC News reported the letter was sent after incidents left staff “distressed”, and included comments from the EIS teaching union about stress and threatening behaviour.

That is the ethical quagmire we avoid with clients. Not because the devices are technically clever, but because they are accessible. The risk is demonstrated not by honed hackers, but by everyday people who decide their personal circumstances justify invading someone else’s privacy.

What organisations can take from this

When we point out that a room bug was planted, photographed, and removed, we are usually assessing the risk based on ease of use and low cost of entry. The impact can be hard to predict. The likelihood is often higher than people expect.

If you are running sensitive meetings, it is worth treating covert recording as a practical risk. Set expectations on recording, keep tighter control of visitors and unattended spaces, use suitable rooms for sensitive conversations, train staff on what to do if they suspect a device, and escalate concerns through a clear internal process. This is basic physical security hygiene, but it matters because the barrier to misuse is so low.

To the person who was recorded before I bought that device, your secrets, whatever they may be, are safe with me. The recordings were deleted.