In some schools, the autumn term is often called “germ-term” due to the number of bugs the children bring back after the summer holidays. It usually calms down after a few weeks, however, with hacking there is no slow down. Its all year, its relentless.

In the last 10 months of this year schools have had it tough, having to deal with covid-19 related lockdowns, underfunding, and a massive increase in cyber-attacks.

Unlike in business, cyber security in schools is often overlooked, IT as a whole tends to be carried out either by external contractors or a teacher who has a bit of IT experience. This has led to a significant rise in targeted attacks against schools, and one of the most common is ransomware.

Ransomware

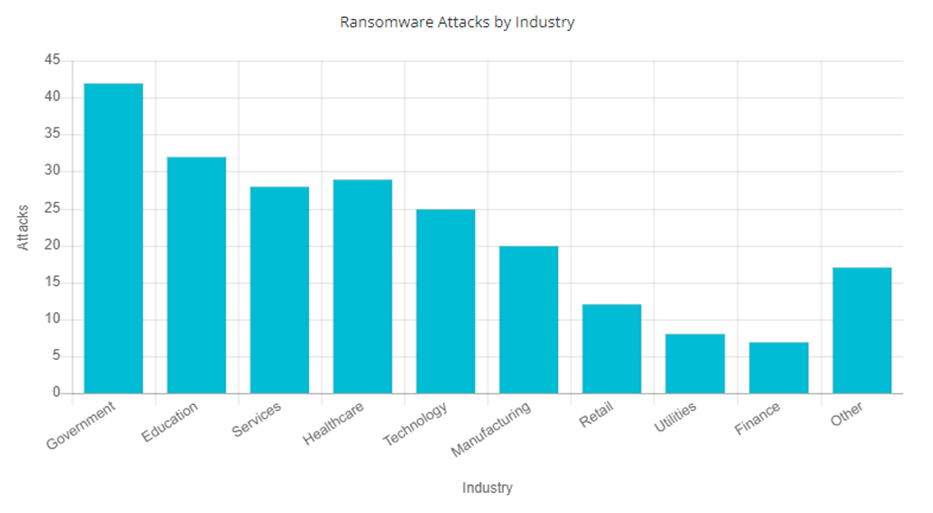

You might be forgiven for thinking that attackers would leave schools alone because they are usually poorly funded or charitable organisations. The truth couldn’t be further from that. Schools are targeted, a lot. The BlackFog ‘State of Ransomware 2021’ report showed that schools are the second most targeted industry behind Government.

Image source: BlackFog

In Spring 2021 Castle School Education Trust in Bristol was attacked and 24 schools had lessons and parents evenings cancelled. In May 2021 an attack against Moor Park School in Preston resulting in 10GB’s of data being leaked, including numerous documents related to student absence, personally identifiable information and medical records.

The school downplayed the data loss in parent mailings “We are aware that some data has been taken by the attackers, but early indication is that this data was not sensitive or confidential and it has not been published.” In July the Island Education Federation in the Isle of Wight reported a ransom attack, this led to at least one school delaying the start of the new school year by 3 days. The impact is significant, but how does it happen?

Modern ransomware works as an affiliate business. The ransomware group provides the software to do the encryption and exfiltration or theft of data, however, the people actually deploying the software are affiliates, they work for themselves and using access they have obtained they deploy the ransomware.

The ransomware group then open dialogue with the victim and agree a ransom fee. Once it is paid anywhere from 60-90% of the fee is paid to the affiliate, with the group retaining the rest. It has been extremely profitable with ransoms commonly over $1m being paid. However, the average payment sits at around $180k, with around 37% paying the ransom. So how does the affiliate get access?

Ransomware is largely a preventable problem. You commonly see a data breach reported with “it was a highly sophisticated cyber-attack”. It rarely is highly sophisticated, indeed, most ransomware is very unsophisticated exploiting basic preventable flaws to gain access. The majority of ransomware attacks start with a weakness your IT team either introduce or do not fix. The most common attacks begin with either, allowing Remote Desktop Protocol (RDP) to be accessible publicly, missing critical security patches on key products such as web servers, VPN, firewalls/Routers or phishing attacks.

Security updates and misconfigurations

The time between when a vendor releases an update for a service and attackers exploiting that is narrowing. Organisations now routinely have hours not days to apply the updates to mitigate the highest risk flaws before they are exploited by attackers.

Commonly schools will expose RDP publicly to cheaply and easily allow staff or students to access services remotely. When you expose RDP to the internet attackers will begin to attack it within minutes. Using a list of usernames and passwords, attackers will try them all against the service, if one works login – game over. There is no two-factor authentication (2FA) for RDP. Default or weak passwords are common, we regularly find Windows systems with administrative passwords of “password” or “admin”. If that service is publicly available through RDP, attackers can trivially access your network without needing 2FA.

Another configurational challenge in schools is passwords, not only do staff not want longer passwords, but they actively discourage longer passwords being set for children. This leads to children having weak or easily guessable password for key systems.

Whilst the intended access with these passwords is usually only a certain service, if you use Office 365 and give your children email access by default they can then access Azure Active Directory, OneDrive, SharePoint and many other applications. With Azure Active Directory users can add up to 20 devices to the domain with no additional rights needed, so now the attacker can add their own device to your domain to make stealing data easier.

Phishing and Smishing

Another very common attack affecting schools is phishing, most schools have an email service usually from Google G-Suite or Microsoft Office 365, both have built in security controls. These need management and configuration. This is regularly overlooked and phishing sneaks through the control. You are then reliant on desktop AV controls and web proxies to make it harder for attacks to succeed. But, what about your staff’s mobile phones?

Earlier in the year there was a surge in SMS-based phishing or Smishing. Commonly masquerading as delivery service scams, victim’s personal data was stolen and used to steal their identity. However, attacks don’t stop at delivery scams. Staff can access resources on their phone, be that a company provided one or a personal one. They can all receive SMS. It is trivial to send an SMS to a mobile with a spoofed sender.

The message will actually show up directly below any other legitimate messages. There is no control to scan the message for spam. There is unlikely to be controls to prevent users clicking the link and loading the webpage. The browser will commonly hide the URL to give more screen space, making phishing attacks appear more legitimate. It’s a highly successful attack method, attackers have around an 80% success rate with smishing, this compares to around 30% for traditional email-based phishing.

An attack can look to steal user credentials to gain access to email and other Office 365 resources, such as OneDrive or be used to access VPN services gaining a foothold in the network.

Treatment

Fortunately, the fixes for these problems are not overly complex, good cyber hygiene is critical. Key controls include:

Never publish RDP directly to the internet – use a VPN to allow staff to connect first. If you can’t do that set up a Remote Desktop Gateway or an Azure Windows Virtual Desktop behind a 2FA protected logon.

Monitor for updates to servers and applications, apply updates as soon as they are released – Many online vulnerability scanning services offer community editions to allow you to regularly scan a small internet presence, these tend to be limited, but are usually free of charge.

Implement strong passwords – ensure complexity is turned on, increase the length to at least 9 characters (ideally longer), with at least 14 for administrative accounts. You may get some complaints from management, however, in my experience taking a 5000-user estate from 6 characters, no complexity requirement to 8 characters with complexity the impact was non-existent. About 3 people raised a ticket!

Enable 2FA – this will need consideration, if you don’t provide staff with a mobile phone, they may not want to use their personal one. There are options available. The security benefits from enabling 2FA are massive.

Train your staff on attacks – do not underestimate how critical staff awareness training is. There are many training services, many are terrible. Shop around for one that works for your culture, a mix of online learning and face to face is sensible. All staff, INCLUDING teaching staff need to do this.

Cyber-attacks are rarely “highly sophisticated” and the mitigation is rarely “buy an expensive security product”. The most effective controls are cheap, often free, and easy to install. The challenge is ensuring you manage the security tools and techniques you have, in a school where there may not even be an IT person, let alone a security person, that can be hard. However, explaining to your faculty, parents and the information commissioner you have been breached, one could argue would be significantly more challenging.