Heading back to the airport to sit in another 747 pilot seat chair is always exciting. After our first research session on a grounded airplane this time we spent more time looking at the IFE (In-Flight Entertainment system).

We found very different results from the first plane. Rather than an old Windows NT OS from when the plane was originally built, in its place was an up to date Ubuntu server running Bionic Beaver. It appeared that a refit of the kit running the IFE had been done in the last few years, as this version of Ubuntu was released in 2018!

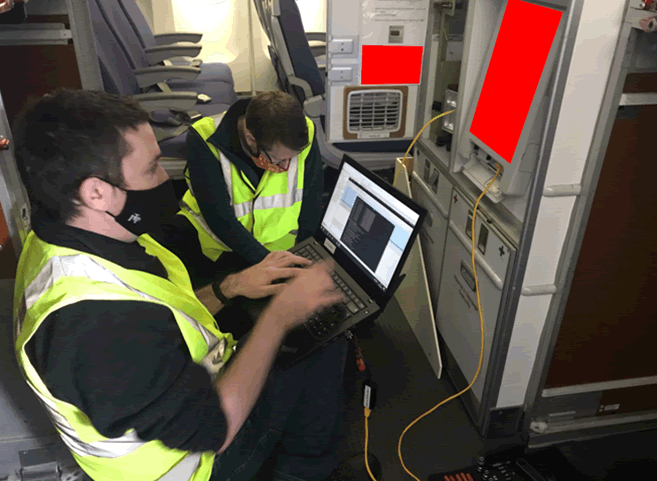

Similarly to the other planes that we have looked at, there was a Cabin Management Terminal (CMT) with an exposed ethernet port available under the stairs with the server kit.

TL;DR

- Limited access was gained to the IFE system.

- As expected, the IFE did not connect to any more sensitive systems on the plane.

- We achieved partial access to the IFE in the time available.

- We also discovered credentials to cloud-connected systems likely used to update media content on the IFE when back on the ground.

IFEs are often updated during ‘heavy checks’, after several years of service. Whilst upgrades are expensive, weight can be saved, passenger experience gets better and improved airborne connectivity can generate revenue.

For us, this meant that instead of investigating the security of an old operating system, we needed to reassess and attempt new methods to gain access.

Connections

Similarly to the other planes that we have looked at, there was an ethernet port available under the stairs with the server kit. This allows direct connection into the IFE network from a logical location next to the equipment, it also allowed the food prep areas to be used to put a laptop on, which was a nice touch!

As this plane was retired, there were no cabin crew to question us: this degree of unfettered access simply wouldn’t be possible in the real world.

We did however find an additional ethernet port that was connected to the same network in a more unusual place. This was in the avionics bay below the passenger area, this area is home of all the tech on the plane and could be accessed either from a hatch in the passenger area or a hatch on the underside of the plane. Again, airside physical security controls are going to make access to the avionics bay all but impossible for unauthorised personnel in the real world.

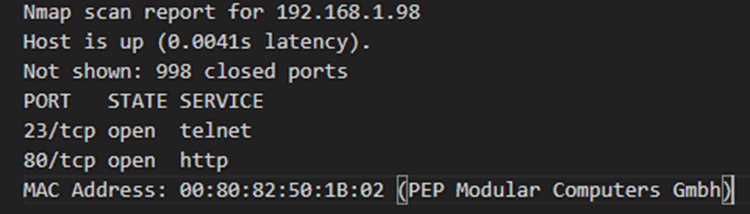

Both these ports provided a connection to a flat IFE network, which all the systems connected to. A port scan of the range resulted in numerous ports over 9 different systems, with the main IFE server having HTTP and Telnet open.

No additional ethernet connection locations were found throughout the plane and it’s important to note that the avionics bay had an ethernet connection for the IFE system and no others, therefore no remote access to the cockpit or flight critical systems was present.

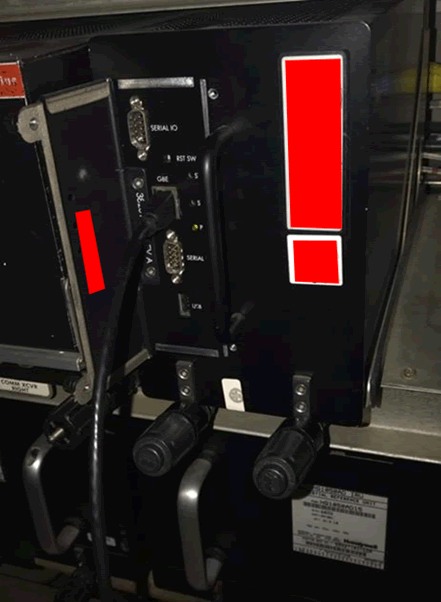

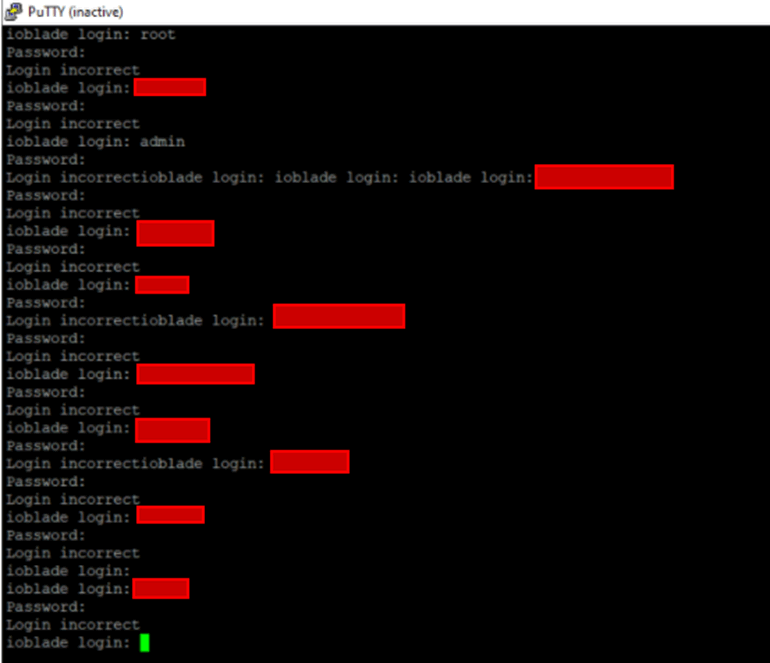

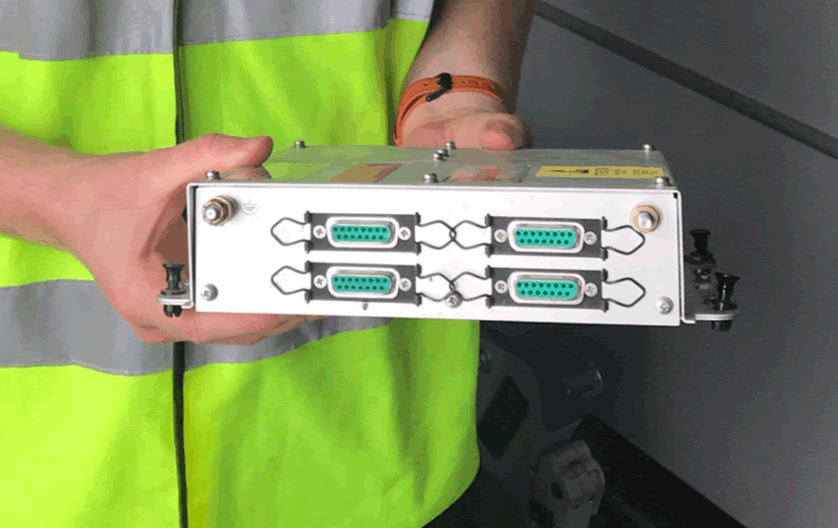

However, within the avionics bay there was a serial connection for the IFE LRU. Once connected, a username and password combination was required, unfortunately for us, neither the default credentials nor brute forcing got us the correct username and password. Given time, we would succeed, but time was against us.

Credentials

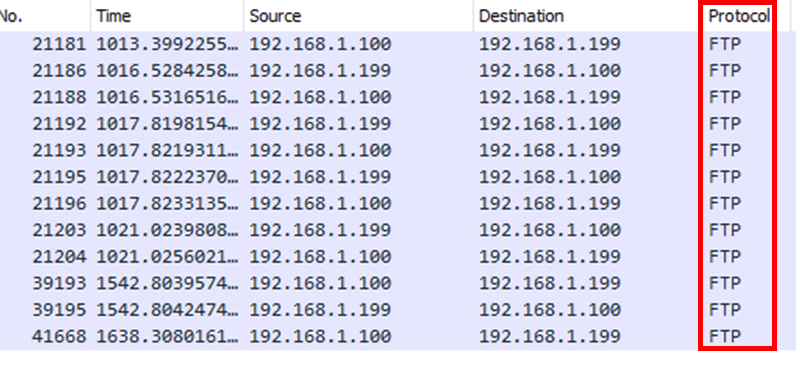

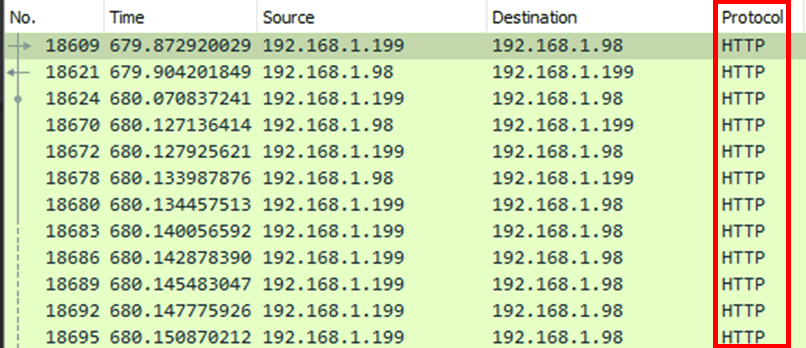

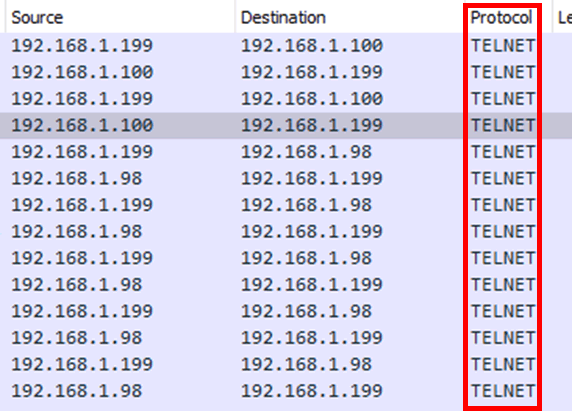

The connection to the IFE network from the cabin management terminal allowed access to different systems, each one was running different services with various ports exposed. Plain text protocols including telnet and FTP were found to be in use on different systems, as well as a web application running over HTTP.

Any credentials for these would be transmitted on the network in clear text, meaning that during normal flight operations it might be possible to capture these credentials.

It may also be possible to sniff credentials from the seat box connections, but this would be practically impossible in flight. Cabin crew would be quick to restrain anyone found doing this:

The seat boxes use custom connectors too, so unless you knew the connector type in advance, interfacing would be nearly impossible in flight. Soldering custom connectors when airborne would be rather…. challenging!

Later seat boxes will feature RJ45 and ethernet, but later IFE usually features much more robust security! Most seat boxes are simply ethernet switches and power supplies, capable of the bandwidth required to stream media.

Although network sniffing wasn’t really an option, there was another avenue which may have yielded further access. Passenger Wi-Fi is increasingly available when airborne, so we weren’t surprised to find a Wi-Fi access point in the galley cabinet where the IFE server was stored.

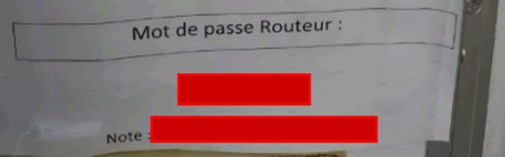

We struggled to interface with the Wi-Fi as it appeared to have been disabled. Interestingly, the password to the router was on the inside of the door to the cabinet in which the AP was stored.

These instructions included a password and a note about how to use the password. The password wasn’t complex and would be crackable by a determined attacker, it’s also likely that the same or similar passwords are used across the fleet, although we cannot confirm this.

However, unfortunately for us, this password was no longer in use. It’s unclear if this was due to the password being outdated, or if all systems had been updated with new passwords since the plane had been retired.

Access

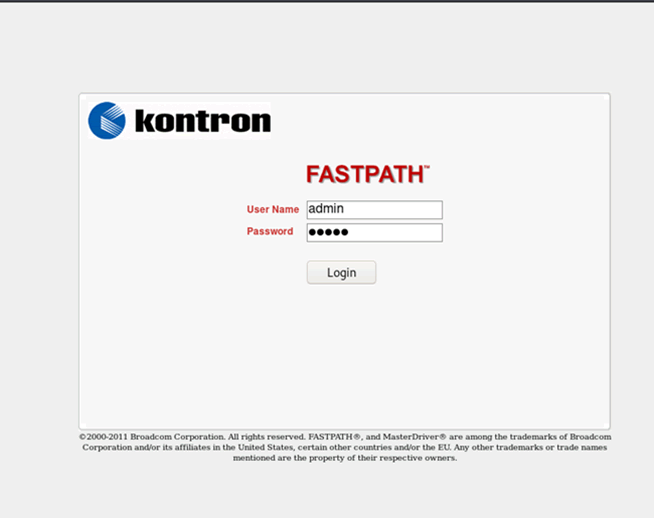

Without any network traffic to sniff or default passwords being in use, further attacks were required, such as brute forcing and searching for available directories. The main IFE server had a webserver running on port 80 running software called FastPath

Credentials were required and again no default or easily brute-forced credentials worked. Looking at the server in more details revealed a second webserver being run on port 4000. This webserver didn’t require any credentials and returned a network diagram of the IFE network.

These network details were available to anyone on the IFE network, be it plugged in directly or over the Wi-Fi connection. The network information shows what is in use with the amount of traffic going to each endpoint and the IP address ranges. This allowed us to further map out the network and ensure we were inspecting all available hosts.

In addition to these web applications, a further one was located which was protected by a numeric PIN with no brute force protection. This allowed us to quickly brute force that PIN and gain full access. This provided access to the maintenance application for all the seatback devices. From here it was possible to force the seats into maintenance mode, resulting in all screens displaying their location, MAC address and version numbers:

This could result in some irritated passengers if done at the start of a 12 hour flight! Although there is no risk to the flight or plane itself, there could be revenue implications as customers demand partial refunds or frequent flyer miles as compensation.

Cloudy with a chance of S3 credentials

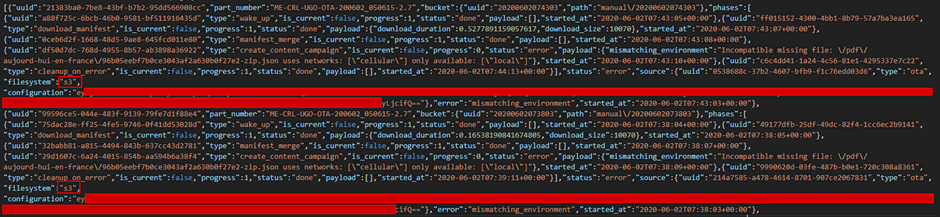

Further investigation into the webservers resulted in additional pages being accessible to unauthenticated users, one of these pages was a campaigns.json page. This page was accessible by anyone on the IFE network and contained some configuration data, with the keyword “s3” and base64’d data.

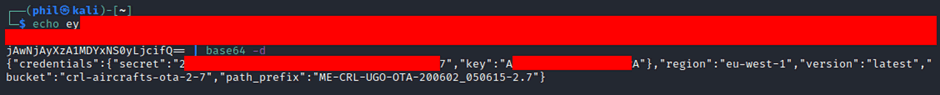

The term s3 stood out immediately as an AWS S3 bucket, a cloud storage account that must be used by the IFE system. The configuration data was put through a base64 decoder and resulted in the AWS secret and key:

This would allow connection into the S3 bucket, which was likely to host daily news video files amongst other files.

It is likely that this S3 bucket is used across the fleet and potentially any carriers using the same IFE systems, replacing the videos on the S3 bucket could result in unexpected content being played on flights which again could result in bad publicity for the carrier.

This issue was quickly resolved when reported to a responsive and responsible IFE vendor.

Conclusion

Access to retired airframes can be sporadic and for very limited time periods. In this case we had about 8 hours access to understand, interface with and assess the security of an IFE that we had never seen before. In many cases, the airframe is parted out before we can get back to it for another research & testing session. Documentation is almost unobtainable outside of the industry.

Further, it’s just an IFE. There is no access to safety critical systems such as the Aircraft Control Domain. One does not simply hack a plane from the IFE!

Partial refits and upgrades of the IFE aren’t uncommon: seat boxes may be left unchanged, whilst passenger displays and servers are much more recent. In this case, the seat boxes appeared to date from the late 1990s, yet the server software was from 2018 and the passenger seat displays from around 2015.

Vendor statement

We would like to take the opportunity to thank the team at Pen Test Partners for their security research regarding one of our products.

The team have been highly professional & diligent with their responsible disclosure; partnering with us to better understand their research and conclusions and in turn, allowing us (the supplier) to provide reciprocal insight.

The continued transparent, open and frank discussions between responsible security researchers and the aviation sectors manufacturers, suppliers and operators can only improve aviation cybersecurity across the entire industry.