TL;DR

- Connected farming kit streams detailed yield data from combines to vendor cloud platforms in near real time.

- That data gives an early view of global crop output and potential movements in grain prices.

- If attackers or insiders can access the yield platform data, they could profit from the futures market.

- Weaknesses in on-vehicle hardware, telematics units and ag cloud APIs make this more than a theoretical risk.

- Stronger access control, hardened devices, better API security and transparent data use policies all help protect both farmers and markets.

Introduction

I live in the countryside & as a result, know quite a few farmers. The subject of connected farming systems comes up quite a lot in the local pub. Those of you who have watched Clarkson’s Farm will understand just how complex and confusing some tractor systems are.

Tractors spend a lot of their time in private fields, so the opportunity for autonomy is significant. The age of robot tractors is some way away, in the opinion of my drinking buddies. Why? Because in the UK, tractors are used for numerous different tasks and fields are comparatively small, hence they spend a lot of time hauling trailers around the local area, among other things. If we simply had enormous fields, robots might work.

What connected farming looks like from the cab

I’ve spent time in the cab of combine harvesters and forage harvesters. The degree of autonomy is significant, as is the connectivity. Steering is automatic; laser and/or GPS guided. Once a field map is entered into the guidance system (usually by driving the perimeter in the vehicle or loading a high-precision map), the vehicle can do just about everything, other than turn at the end of each furrow, though some can already do this.

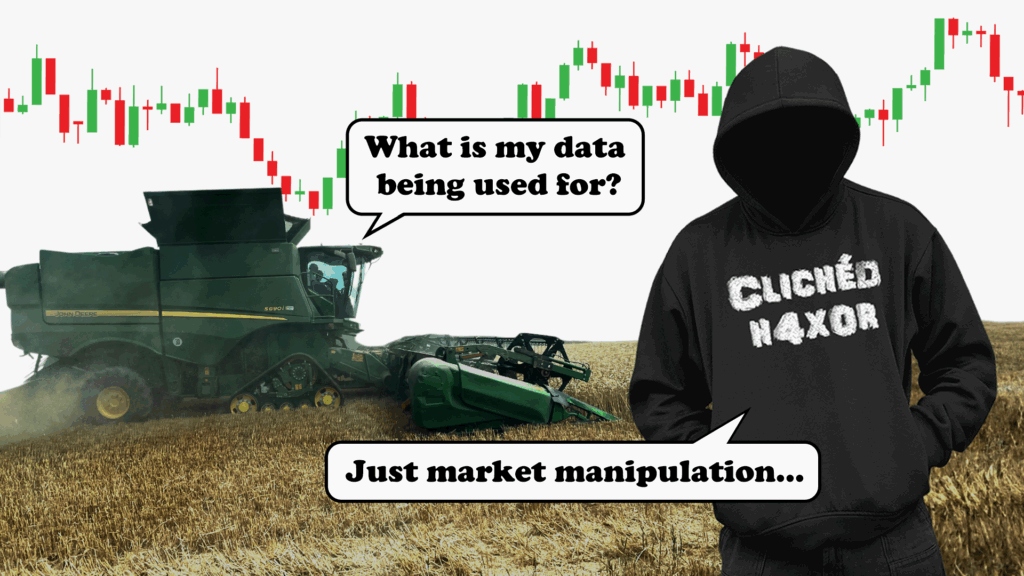

Whilst the opportunity to tamper with steering and other connectivity systems has potential, of most interest to me in that cab is the yield monitor, which you can see in the background of this photo featuring my colleague David Lodge:

That’s the system in a combine that tells the farmer in real time how much crop is being harvested. How many tonnes per acre /hectare are being harvested? That’s a critical data point for any farmer – how much money are they likely to make from their efforts over the growing season?

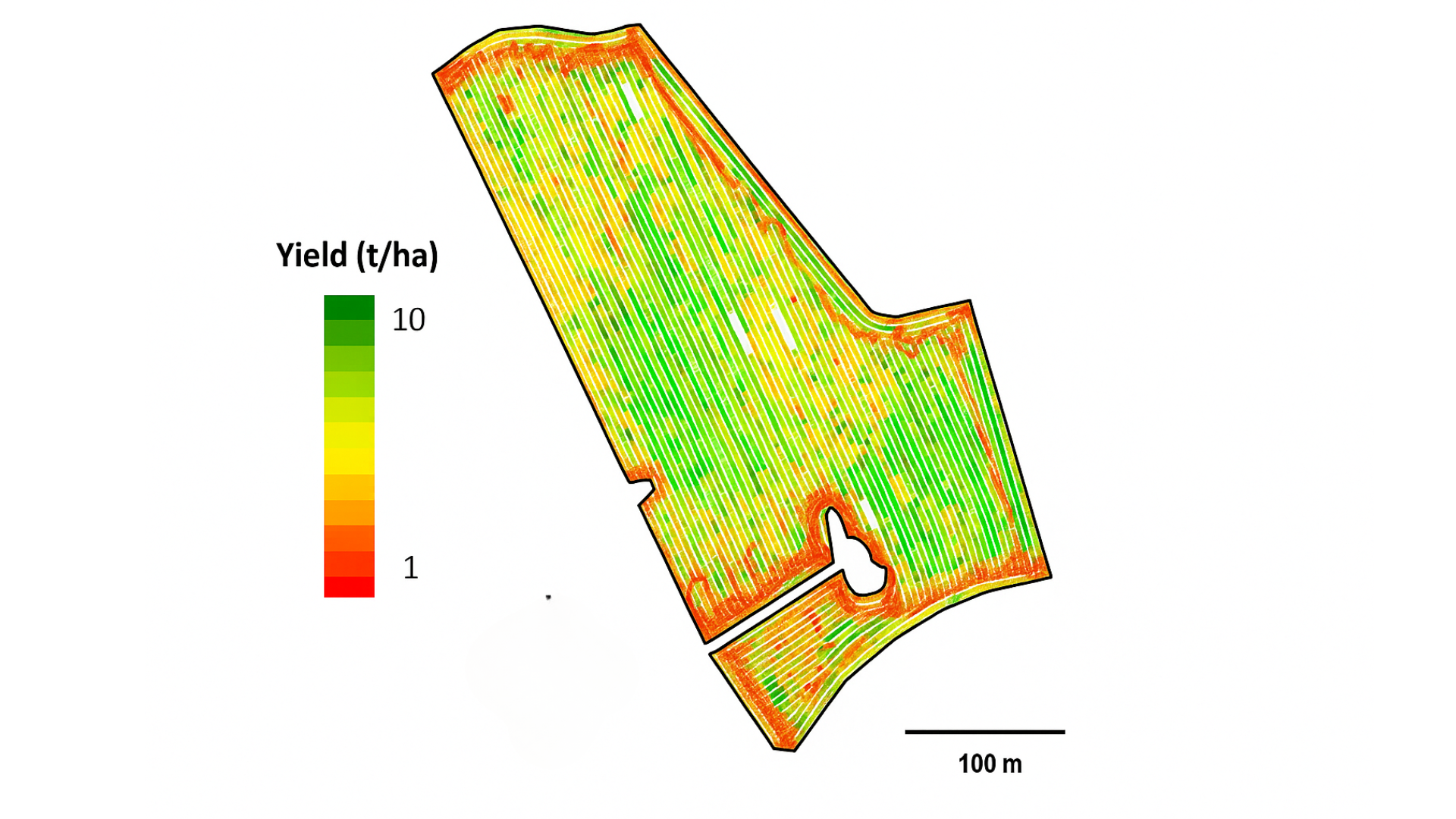

The image below shows an example yield map, with colours indicating the amount of crop harvested from each part of the field. Green areas represent higher yields, while red areas show poorer performance. This data helps farmers understand variability across their land and plan future improvements, such as adding more fertiliser to certain parts of a field to encourage better growth.

Obviously, there are other factors, such as the quality of the crop & the fluctuating price of grain, but that data is critical to the farmer.

But that yield monitor data is key

After a busy day’s harvesting, the farmer can view the data on a PC or mobile device, typically via an API to a cloud platform. The combine harvester has a data connection to that cloud platform also, enabled by a mobile data SIM, not dissimilar to a telematics control unit that you might find in a car.

How much grain did they harvest from each field, and each part of that field? A very valuable data set.

Creating that connectivity from the combine or tractor requires an expensive device. In the case of John Deere, the system is known as ‘StarFire’.

You’ll see the green and yellow receiver on the front of the cab roof. Other manufacturers have similar systems, such as Massey Ferguson’s MF Guide and Valtra Guide. They’re so expensive that they are sometimes stolen to order. One local farmer even had the steering wheel of his tractor stolen along with the receiver, as they are part of the auto-steering setup. A very costly day.

After buying the connectivity equipment or buying a tractor pre-equipped with it, the cloud platform connection is required. The cloud platform subscription is often free though.

It’s an old adage from social media apps: if the product is free, you’re the product.

This got me thinking over a pint with a farmer a while back

If the yield data goes to the cloud platform, a cloud platform operated by the combine harvester manufacturer, surely the manufacturer has access to a LOT of data coming off the combine harvester heads in real time.

The manufacturer would therefore have visibility of the crop yield across every field on every farm across the world before anyone else.

Now we understood why the service was free: that data would allow the combine manufacturer to know crop yields before the market did.

The opportunity to take a long or short position on grain futures was huge! We’re not suggesting that the manufacturers actually do this, but the temptation would be significant.

Yes, weather and growing conditions would be known in advance, but the exact real-time yield data across continents was very valuable indeed.

Then the evil hacker in me got thinking

Remember the 1983 movie ‘Trading Places’ featuring Dan Aykroyd and Eddie Murphy? The crux of the movie involves feeding incorrect orange juice harvest data to a commodities brokerage firm who have carried out a social experiment on the two stars. Revenge is sweet, as the brokerage acts on the wrong data, tries to corner a market that is actually flooded with FCOJ and bankrupts itself.

It would take some aggregation, either by feeding incorrect data from a large number of combines, or if a vulnerability in the cloud platform could be exploited, perhaps through one of the many API authorisation flaws we’ve found in connected systems over the years. We’ve also found issues in telematics platforms during pen tests on numerous vehicles before. Any one of those could be a sufficient route to cause misleading data to be fed to the manufacturer.

Is this likely to happen? I hope not, but it’s an interesting thought exercise around unexpected financial consequences of connectivity.

How might we mitigate this style of attack?

Basic cyber hygiene first: ensuring that anyone with high privilege access to the cloud platform has strong passwords and MFA. Additional security controls would help, such as restructuring access to administrative interfaces also.

Securing physical hardware is also key – don’t let the device on the combine or tractor become a route into the cloud platform. We found exactly this issue in a test described here.

Aggregated, anonymised data used to improve products or offer benchmarking is a different question, but even then the manufacturer should be open with farmers about how their data is used.