In the 1980s and 90s , there were a significant number of bulk carrier losses attributed to inappropriate loads placed on these ships. Bulk carriers are completely different to container ships: we discussed the vulnerability of these to load plan hacking in this post.

One of the most high profile losses was the MV Derbyshire which disappeared at sea with the loss of all hands, only located on the sea bed 20 years or so later. Investigations much later concluded that excessive stress as a result of flooding during heavy seas caused it to break up.

A colleague of mine was an officer on board a sister ship of the Derbyshire at the time; the very same design, so concern about design, loading and hull stress was top of mind for a long time after. Two other ships of the same class of six also experienced structural issues; MK Kowloon Bridge and MV Tyne Bridge

To address mounting bulk carrier losses, hull stress monitoring systems (HSMS) were implemented in order to ensure stresses did not exceed design specification

Loading bulk carriers

HSMS has two different purposes – first to deal with loading in port, second to deal with load at sea. A vessel can usually deal with higher strain whilst stationary in calm waters compared to riding out a typhoon!

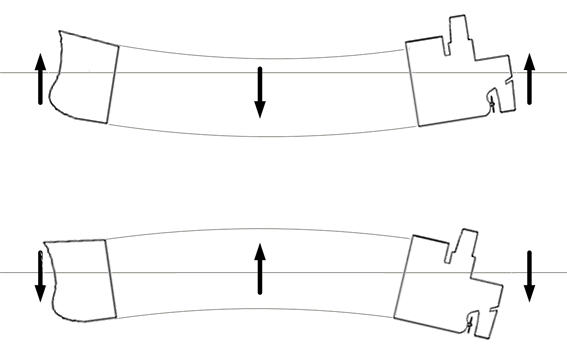

Loading has to be done carefully. Loading one bay in its entirety whilst the others are empty can cause sagging (top) or hogging (bottom):

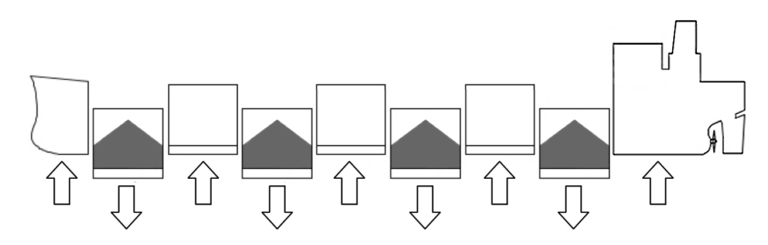

It can also put excess stress on the ship frames, sides and between holds if not done evenly. When loading a dense cargo such as iron ore, it’s surprisingly easy for this to happen:

Shearing forces can also be enormous if loads aren’t thought through:

If a carrier is making multiple calls en route to collect loads, one can see why there’s a temptation to load unevenly – one bay for one product and a different hold stays empty for the next load to be collected at the next port.

Hacking the HSMS

Loading would traditionally be supervised by the Chief Officer, with little more than calculators and tables to estimate bending forces on the hull.

Nowadays it’s done using electronic strain gauges and accelerometers feeding data to on board monitoring systems.

Alarms are sounded on the bridge if excess strain is detected, alerting the crew to take action. The data is also fed to a Voyage Data Recorder or VDR, usually over an IP network

Most of these are just rugged PCs… Connected to the ships network….

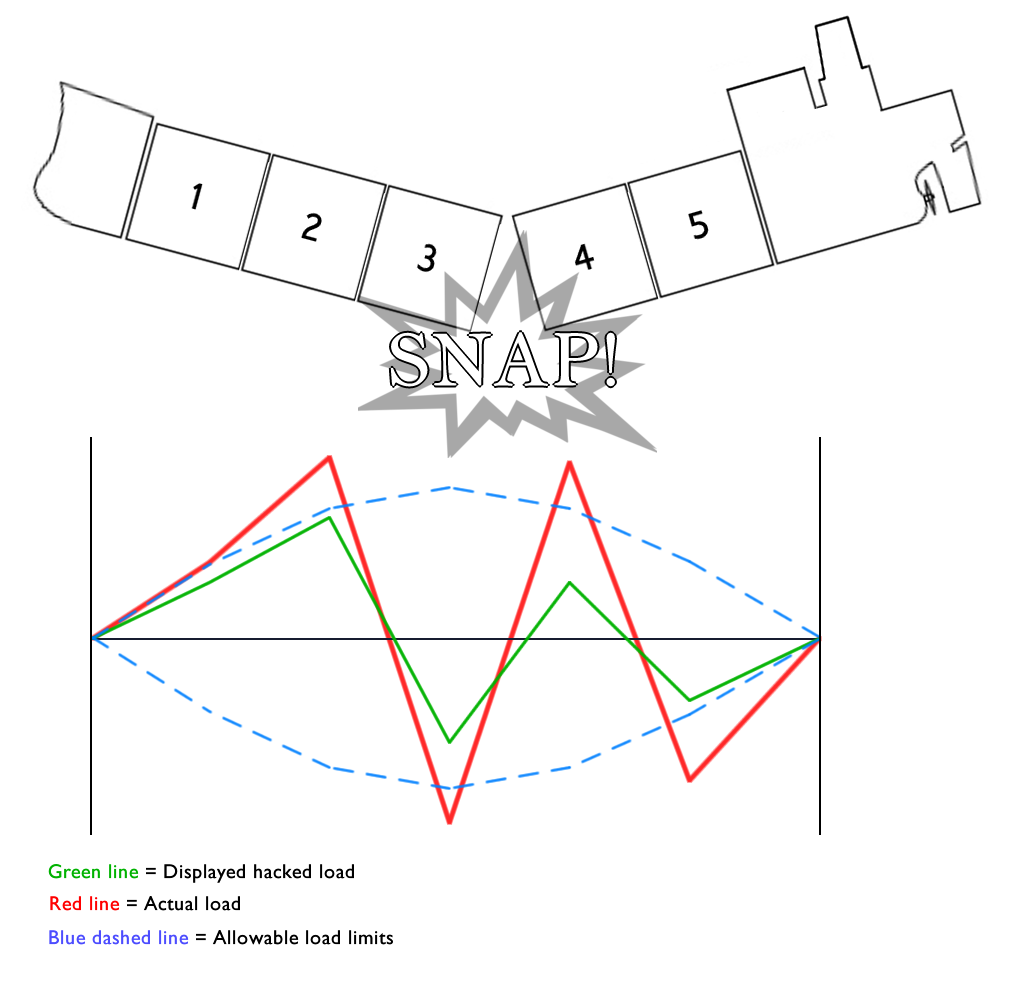

Want to sink a bulk carrier? Just interrupt or manipulate the loading data being fed to and from the monitoring system, having previously compromised the network either via the satcom unit or a phish. This is what the manipulated data shows, everything nicely within tolerances.

The loading continues, without any stress alerts being sounded. The crew are oblivious of this, as they rely on the automated stress monitoring systems. This is what is actually happening, everyone is oblivious until the boat snaps in two!

Actual load, misreported:

Advice?

Security concerns weren’t on the radar of HSMS vendors when they were first designed. Why would they be? They’re just monitoring hull stress.

Ships were isolated when at sea, only a malicious crew member would be able to attack the system. Why sink a boat that you’re on board! Now however the ship can be accessed remotely, via the internet, and through the satcom system.

HSMS vendors, indeed all ship control & reporting system manufacturers need to take security very seriously indeed, otherwise their own system can be turned against the ship.

The ships master puts his faith in the stress monitoring system to alert to excess stresses; the last thing they expect is for it to mis-report and threaten the fabric of their ship.

Ask probing questions of your technology and control systems suppliers; demand that they prove to you that their systems are secure and will remain secure throughout their operational lifespan.