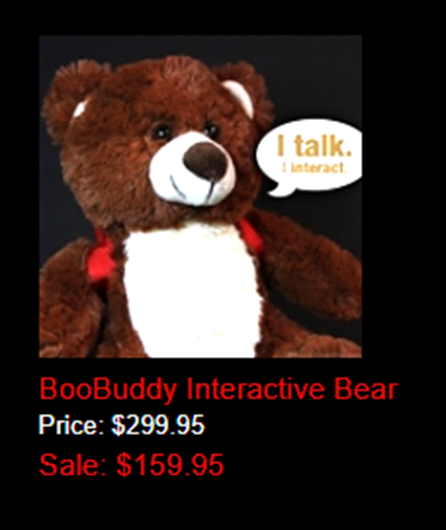

The “Boo Buddy” is sold as a “trigger object” with a wide range of internal functionality such as EMF, motion and temperature detection. It’s a “trigger object”, in the sense that it is designed to evoke the spirits of children, who might be drawn in by the presence of a toy. Many people have reported positive findings from using this guy, and it was exciting to finally get to see one in the flesh.

There’s not much we know about a device like this. All we want to know, really, it whether it actually does what it says it does. There’s no point spending hundreds of dollars on a device which won’t actually deliver.

The Externals

The bear itself is pretty friendly looking! You can see why child ghosts might want to interact with it.

The Boo Buddy front.

The Boo Buddy rear – the backpack’s for the batteries.

Since the bear itself is just a sheath, covering the real electronic internals, we’ve got to open it up somehow to see what it’s actually made of.

The Internals

The backpack has just got the battery holder in – nothing too interesting there.

Its actual internals are accessible through a small hole in the back of its upper thigh, plugged by a 3D-printed seal of a ghost, glued to the material.

After a bit of careful massaging, it’s possible to remove the bear’s technological guts through this small opening.

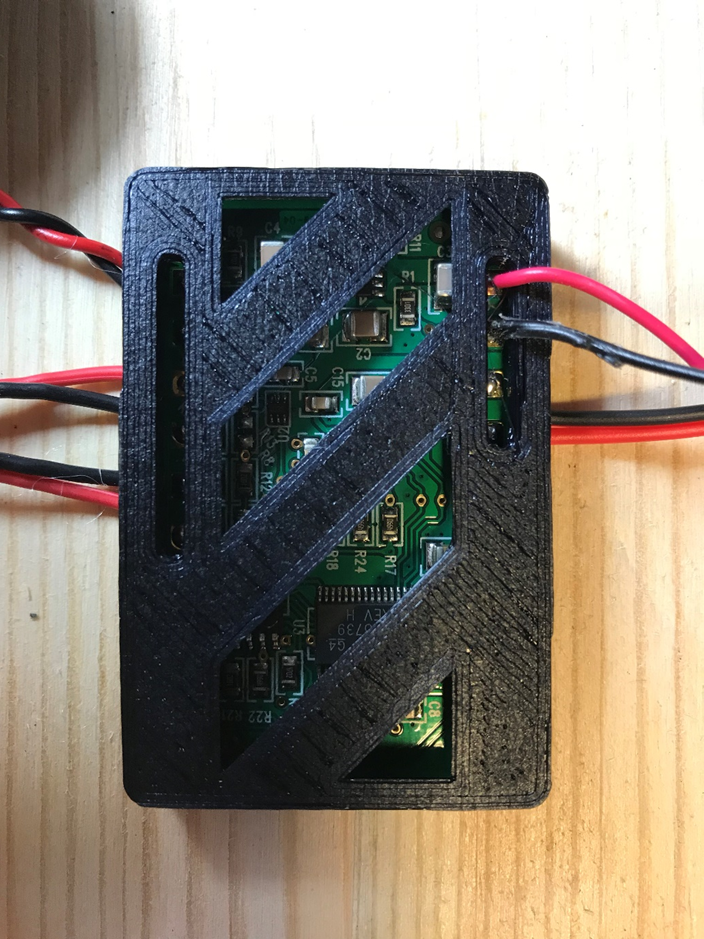

The PCB comes in a 3D-printed case, which also seems to double as a form of tamper detections (we’re never getting our money back for this now, sadly).

The board in the 3D printed case.

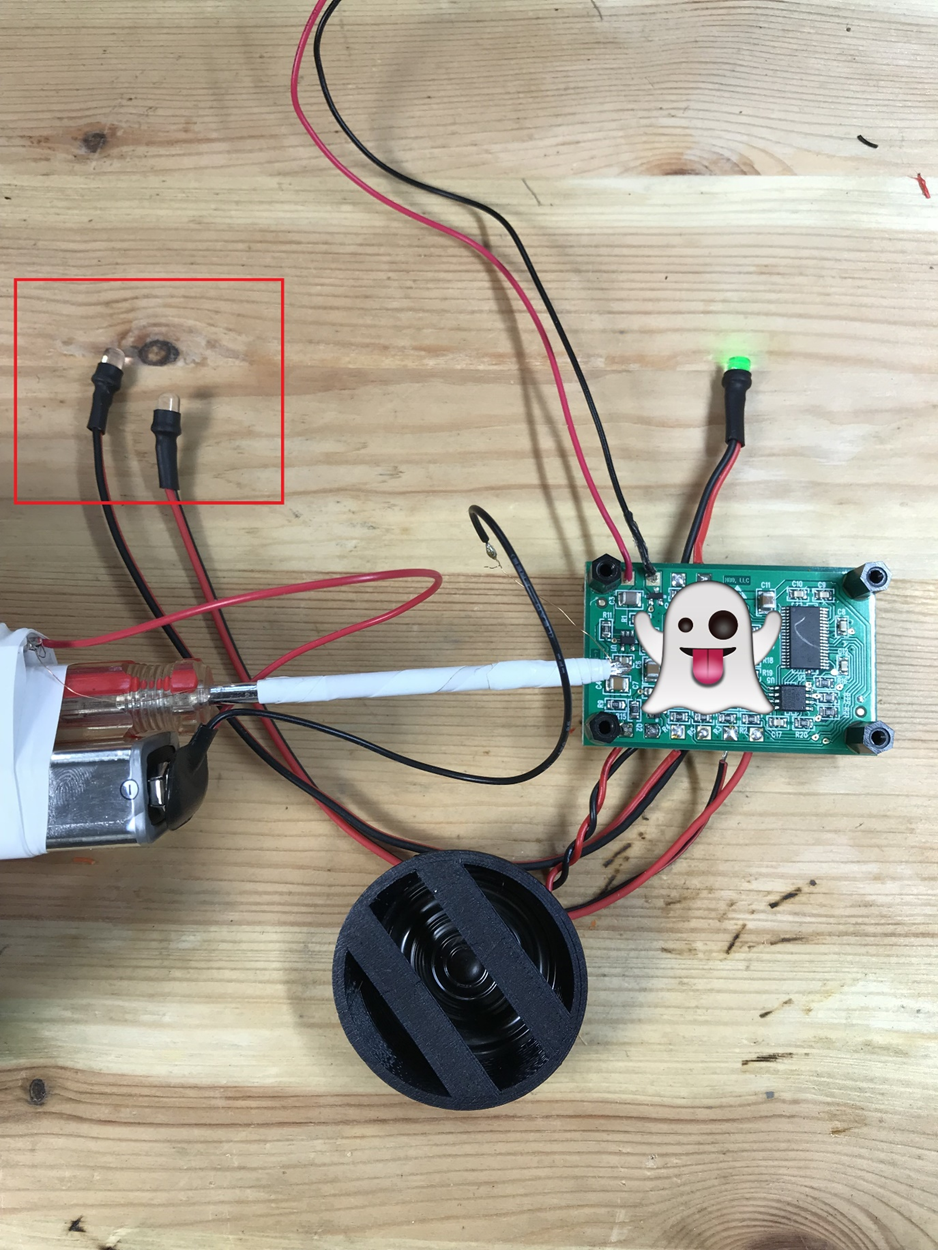

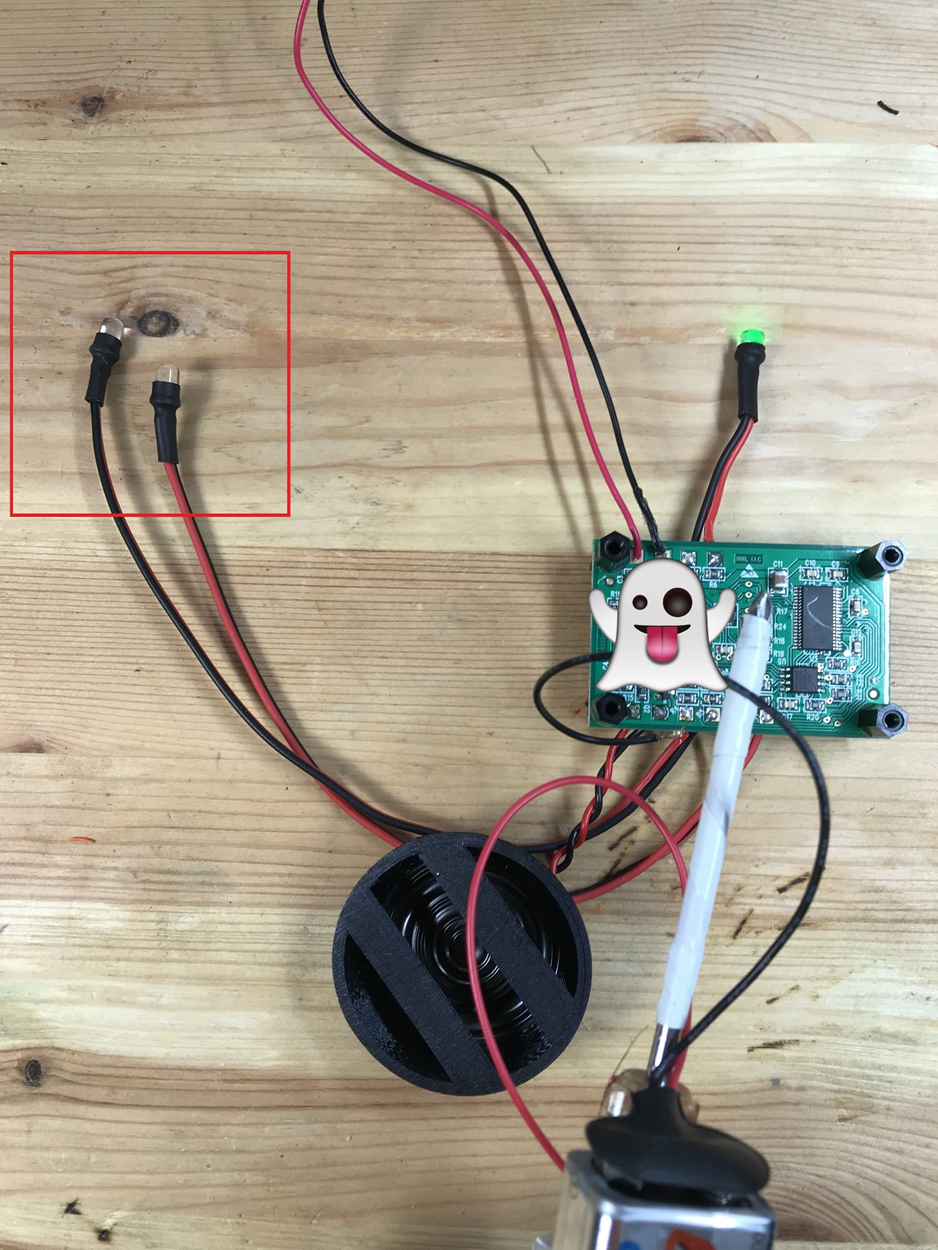

Three LEDs and one speaker are peripheral to the board. The short-cable LED is green, and denotes that the device is switched on. The two longer-cable LEDs are red, and supposed to indicate when changes in temperature, electromagnetism or movement are felt.

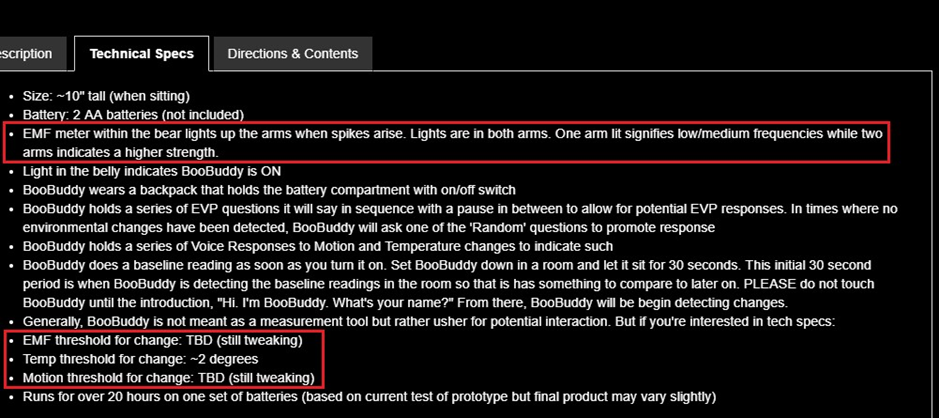

The spec sheet on the website tells us roughly what’s supposed to happen with this device.

However, it’s not very specific about the EMF and motion detection thresholds.

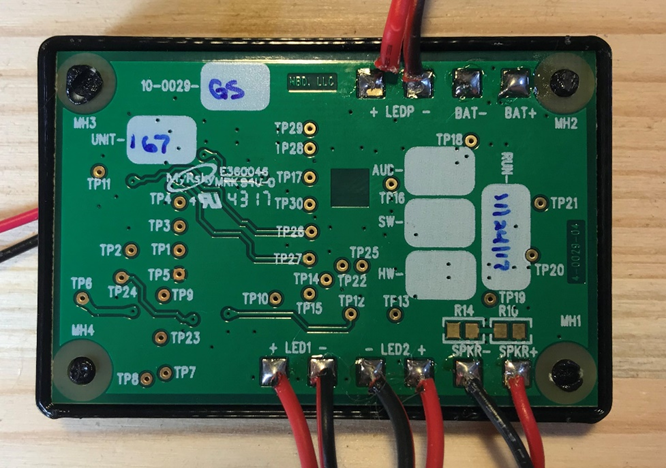

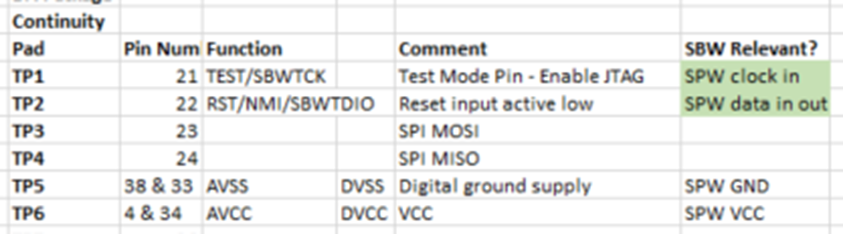

Test pads exposed on the rear of the board.

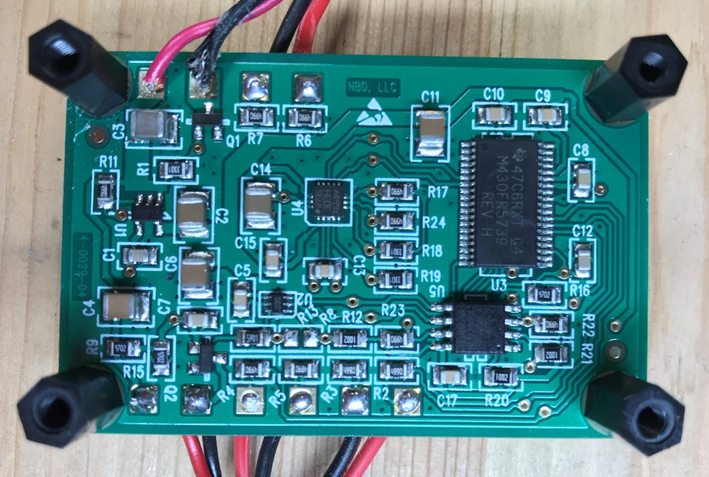

After some “negotiation”, the PCB was removed from the 3D-printed case. This gave a better view of the functional internals.

A quick snap of the “business” side of the PCB. Some 3.5mm plastic fixings were attached to the board to make it easier to handle. There’s not a huge amount to look at, really.

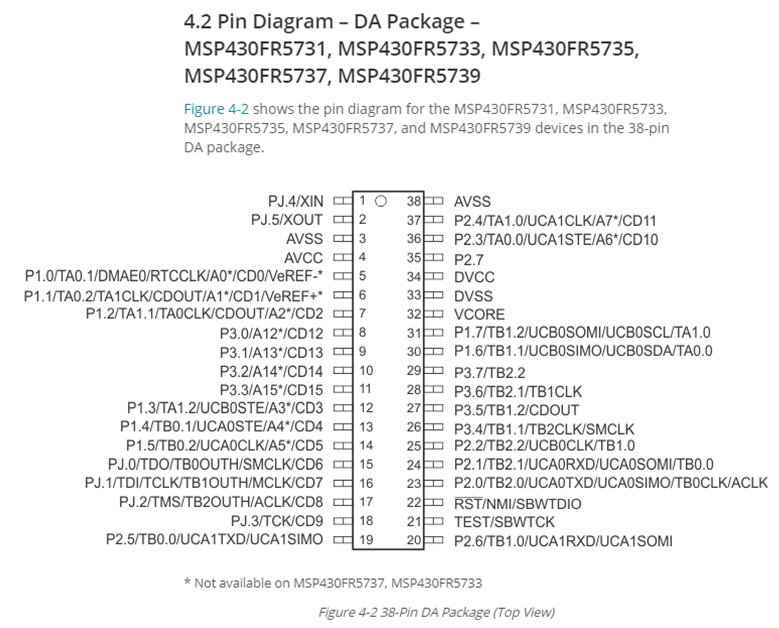

The device appears to run based around a Texas Instruments MSP430FR5739. This is quite a common microcontroller, used in various kinds of embedded systems.

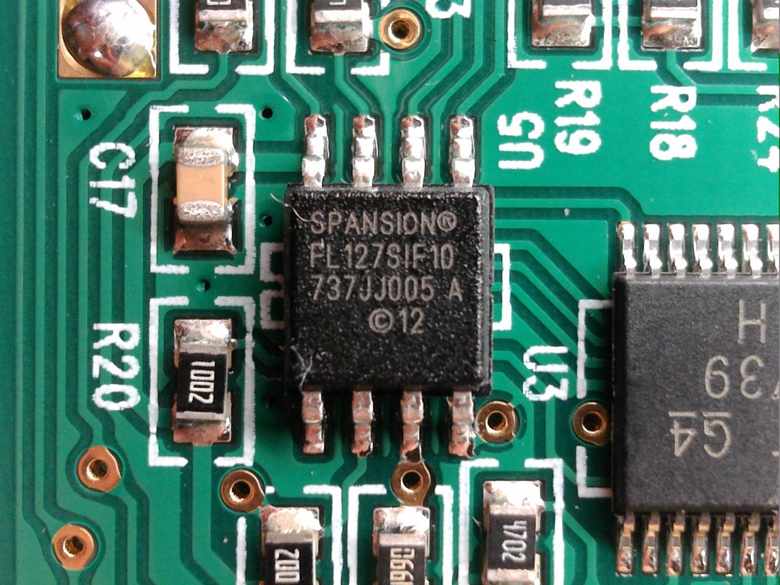

A Spansion FL127S SPI flash chip.

There’s an SPI flash chip, holding the audio recordings and some bytecode, by the looks of it.

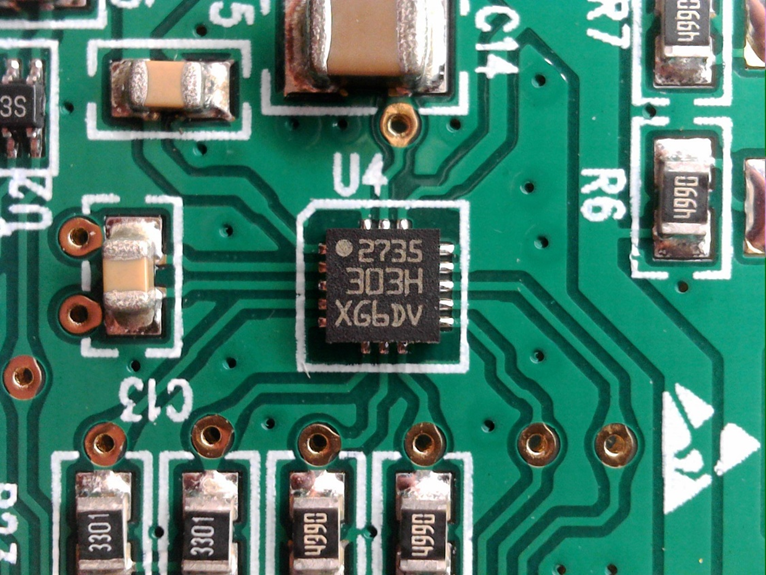

There aren’t any other interesting looking ICs on the board, other than what looks very much like an LED driver. I was really expecting to see a copper coil for detecting EMF, or even some kind of special EMF detection IC. There was no obvious EMF detection functionality on the board at all.

Probably an LED driver.

Despite there not being many ICs on the board, there was, very near to test pad 30, a glob of sticky compound with what looked like human hair stuck to it.

Probably some human hair.

Closer inspection only galvanised this suspicion.

Human hair? In my BooBuddy?

It’s not particularly important – but it’s a bit weird. It’s likely these boards have been assembled at the vendor’s kitchen table, rather than totally assembled in a clean facility.

The human hair aside, the board is relatively simple. The MSP430FR5739 is the brains, there’s some flash memory for sounds and maybe some code, and an LED driver IC for the peripheral LEDs. There’s also a very basic speaker for playing the audio.

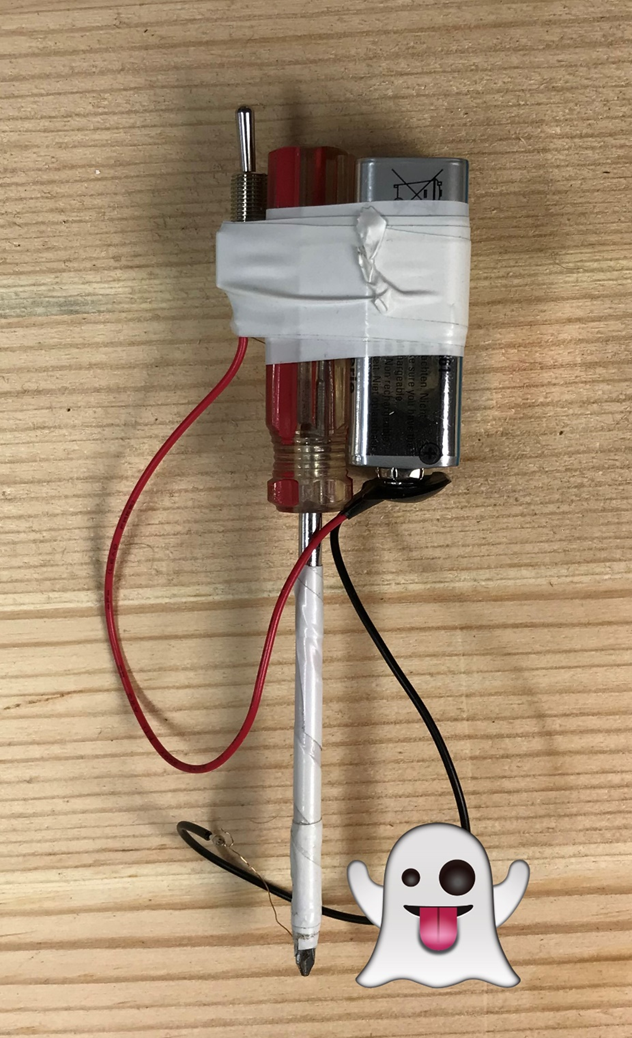

So, despite the lack of obvious EMF functionality, let’s see how it actually performs for detecting EMF! I’ve built a test “ghost” – a very basic electromagnet powered by a 9V battery.

Our ghost simulator

It’s just an electromagnet, but it’s generating some EMF fields. We can make sure it’s working using an actual EMF detector.

Yes, that’s working. If a ghost rubs up right against the detector, we ride into the “danger zone”!

Now, let’s see how the bear board reacts.

We’d expect the LEDs to light up. But there’s no response at all. Let’s try another few angles.

Nope, nothing.

Well, that’s disappointing.

At this point it would be useful to have a look over the MSF430 firmware – to get a sense of what this device is actually doing at bytecode level. After buzzing out the test pads on the back and cross-referencing with the pinout diagram from the MSP430FR5759 datasheet (http://www.ti.com/product/MSP430FR5739/datasheet/terminal-configuration-and-functions#SLAS6392299), we can see which test pads on the back correspond to debug pins on the MCU.

A few of the test pads buzzed out on the board.

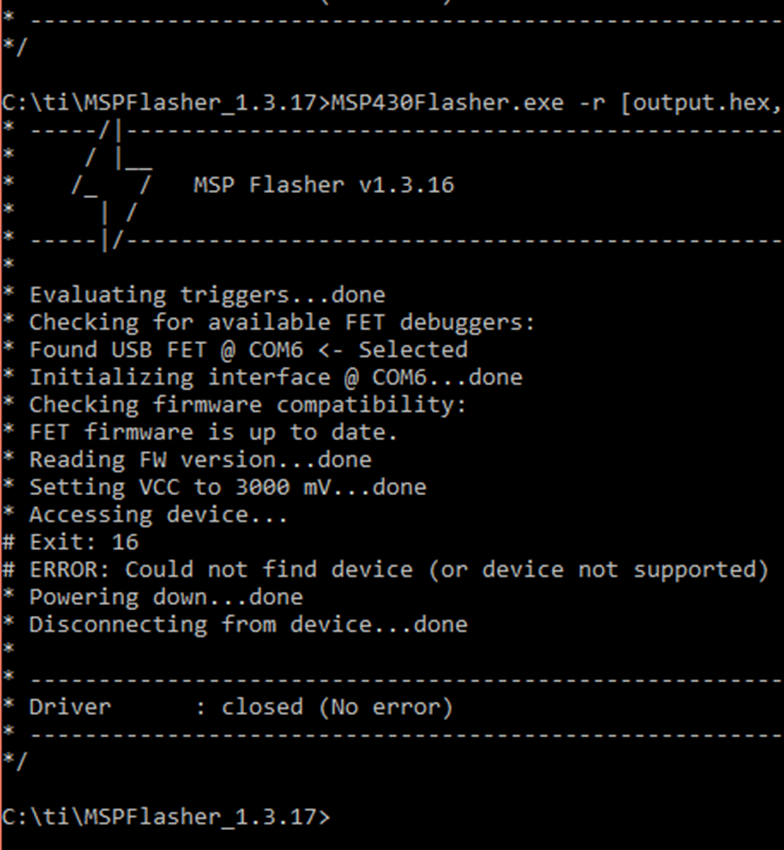

The MSP430F5739 can use the Texas Instruments Spi-Bi Wire protocol. I thought I had the right debugger for this – an eZ430-F2013. Unfortunately, like with most TI chips, it’s incompatible due to some arbitrary edge case technicality.

MSPFlasher can’t find it, so I can’t dump the firmware off it easily.

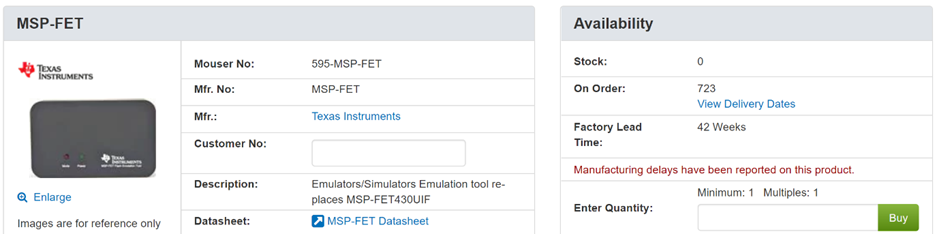

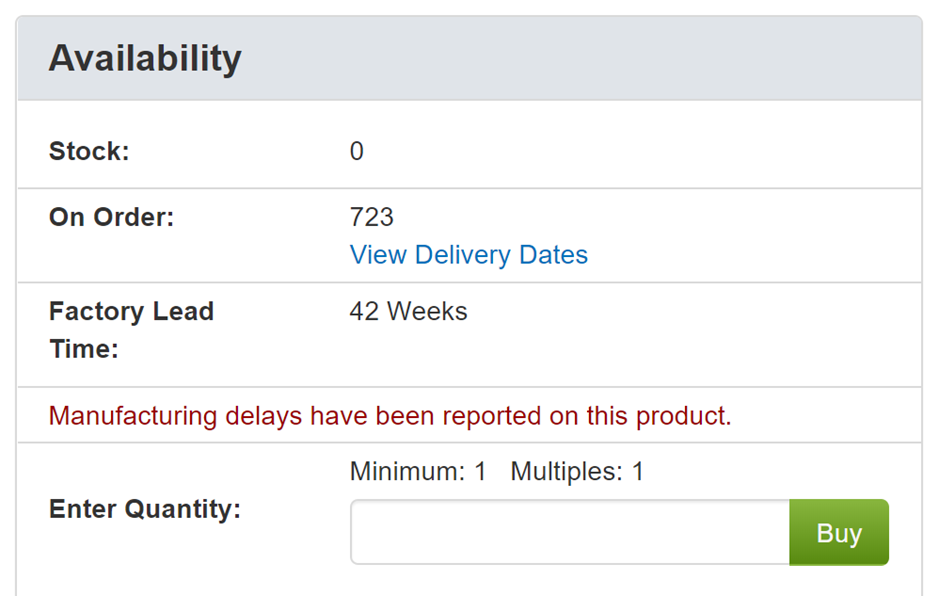

Instead, it seems I need an MSP-FET.

And, again, like most TI problems, this one’s a long one. 42 week lead time for an MSP-FET.

Since this post’s going out some time within the next 42 weeks, I’ve got to find another way to get one of these. If all goes well, we’ll have a part 2 of this – maybe around Halloween.

BooBear Conclusions (so far)

The board BOM can’t be worth more than $10, tops. Assembly, maybe $10 a board? The custom bear itself, from a generic toy manufacturer, probably $10 at most. It probably costs $30 absolute maximum to produce this thing.

The RRP is $299.95. Almost three hundred US dollars. Even on sale, it’s about $160. Plus shipping.

Also – it doesn’t seem to do what it advertises. The board doesn’t appear to have any mechanical method for detecting EMFs.

Maybe you’ve got one of these and it works fine. Maybe we got sent a total dud. But if you’re thinking of dropping a few hundred dollars on catching child ghosts, you’d probably be better off getting a teddy bear from a charity shop and some actual, working EMF detectors, temperature sensors and motion sensors.

There’s also an introduction to Ghost Hardware plus a full review of ghost hunting device No.1 the Ghost Pro, and a review of ghost hunting device No.3, the Ghost Rover.